Our shopping cart is currently down. To place an order, please contact our distributor, UTP Distribution, directly at utpbooks@utpress.utoronto.ca.

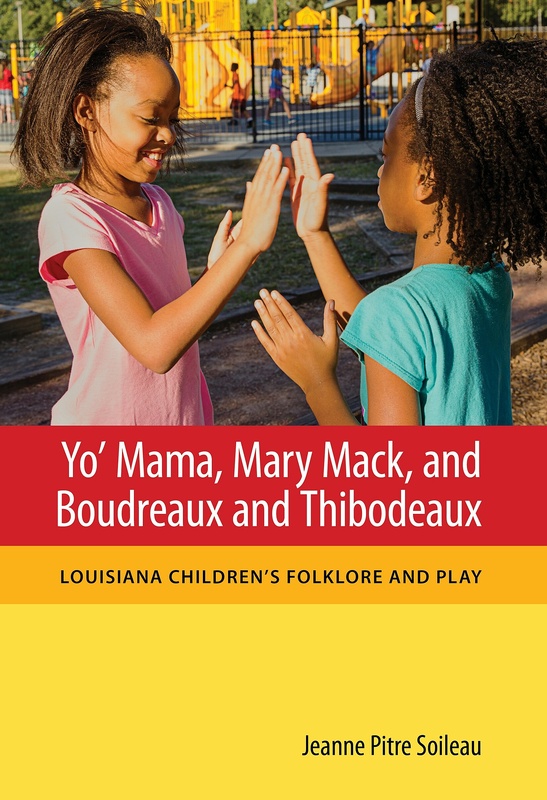

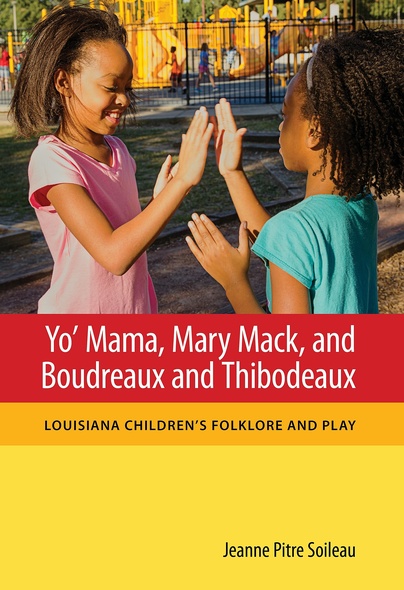

Yo' Mama, Mary Mack, and Boudreaux and Thibodeaux

Louisiana Children's Folklore and Play

Winner of the 2018 Chicago Folklore Prize

and

Winner of the 2018 Opie Prize

Jeanne Soileau, a teacher in New Orleans and south Louisiana for more than forty years, examines how children’s folklore, especially among African Americans, has changed. From the tumult of integration to the present, her experience afforded unique opportunities to observe children as they played. With integration in New Orleans during the 1960s, Soileau notes how children began to play with one another almost immediately. Children taught each other play routines, chants, jokes, jump-rope rhymes, cheers, taunts, and teases—all the folk games that happen in normal play on the street and playground. When adults—the judges and attorneys, the parents, and the politicians—haggled and shouted, children began to hold hands in a circle, fall down together to “Ring around the Rosie,” and tease each other in new and creative ways. Children’s ability to adapt can be seen not only in their response to social change, but in how they adopt and utilize pop culture and technology. Vast technological changes in the last third of the twentieth century influenced the way children sang, danced, played, and interacted. Soileau catalogs these changes and studies how games evolve and transform as much as they are preserved. She includes several topics of study: oral narratives and songs, jokes and tales, and teasing formulae gleaned from mostly African American sources. Because much of the field work took place on public school playgrounds, this body of oral narratives remains of particular interest to teachers, folklorists, linguists, and those who study play.

In the end, Soileau shows that despite the restrictions of air-conditioning, shorter recess periods, ever-increasing hours of television watching, the growing popularity of video games, and carefully scripted after-school activities, many children in south Louisiana sustain traditional games. At the same time, they invent varied and clever new ones. As Soileau observes, children strive through their folk play to learn how to fit into a rapidly changing society.

Awards

- , Winner - Opie Prize

Jeanne Soileau’s work confirms the value of children’s folklore and its on-going study through opening the window onto a remarkable period in a unique region.

In the end, Soileau shows that despite the restrictions of air-conditioning, shorter recess periods, ever-increasing hours of television watching, the growing popularity of video games, and carefully scripted after-school activities, many children in south Louisiana sustain traditional games. At the same time, they invent varied and clever new ones. As Soileau observes, children strive through their folk play to learn how to fit into a rapidly changing society.

Yo’ Mama, Mary Mack, and Boudreaux and Thibodeaux is a testament to the sustainability and adaptability of folklore. . . . an invaluable study of Louisiana’s African American children’s folklore and the intersections of mass-mediated, technological, and folkloric forms of play.

Yo Mama, Mary Mack, and Boudreaux and Thibodeaux will be welcomed by those who yearn for situated, contextualized studies of children’s folklore and by those who are interested in the intersections of mass-mediated, technological, and folkloric play forms. Ultimately, the book stands on its own as a gift to history, for Soileau’s work captures many inflections of children’s folklore in Louisiana that, otherwise, would have disappeared into the past.

Soileau’s work is a critical contribution to the roots and defining elements of folklore in Louisiana. As well, it should be a valuable companion to research and many publications on child’s play.

Jeanne Soileau’s Yo’ Mama, Mary Mack, and Boudreaux and Thibodeaux is a remarkable collection of forty-four years of Louisiana children’s folklore (1970–2014). The extraordinary range of the study gives us a fascinating look at the persistence and innovations of children’s play and young adult performance, particularly in the African American and Cajun cultures of Louisiana.

This book makes a significant contribution to the field, and most importantly with such a topic, it made me laugh, guffaw, and giggle. Covering Louisianan children’s folklore from its European and African roots to the moves of Big Freedia, this is a most unusual compilation that I will welcome to my library.

This excellent study of children’s folklore in post-desegregation Louisiana will make an important contribution to children’s folklore studies and studies of social change in the American South. Folklorists, anthropologists, sociologists, and African American studies specialists will find it to be a valuable text for college classes. The author’s engagement in children’s folklore research throughout the state for forty-four years makes this a remarkable book.

Jeanne Pitre Soileau was born in New Orleans and taught in Louisiana for forty-seven years. Though retired, she is still actively collecting folklore. Her work has appeared in Louisiana Folklore Miscellany and Western Folklore.