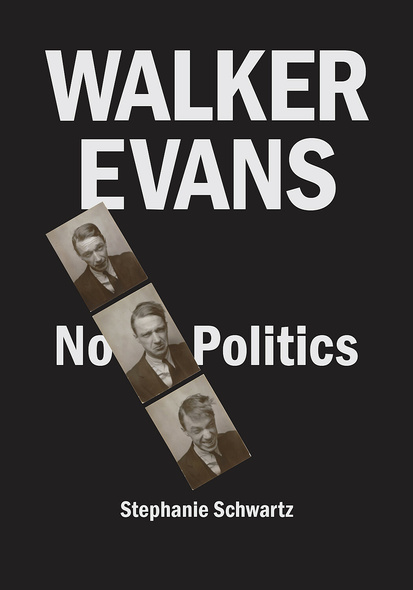

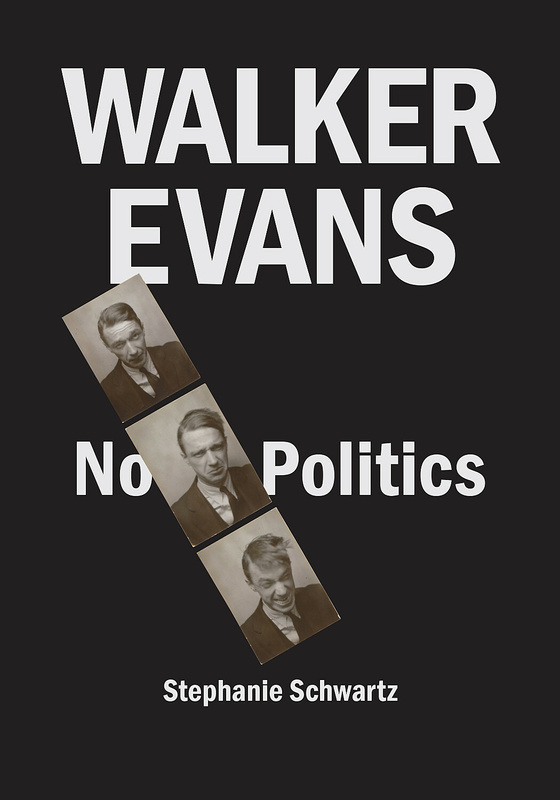

“NO POLITICS whatever.” Walker Evans made this emphatic declaration in 1935, the year he began work for FDR’s Resettlement Administration. Evans insisted that his photographs of tenant farmers and their homes, breadlines, and the unemployed should be treated as “pure record.” The American photographer’s statements have often been dismissed. In Walker Evans: No Politics, Stephanie Schwartz challenges us to engage with what it might mean, in the 1930s and at the height of the Great Depression, to refuse to work politically.

Offering close readings of Evans’s numerous commissions, including his contribution to Carleton Beals’s anti-imperialist tract, The Crime of Cuba (1933), this book is a major departure from the standard accounts of Evans’s work and American documentary. Documentary, Schwartz reveals, is not a means of being present—or being “political.” It is a practice of record making designed to distance its maker from the “scene of the crime.” That crime, Schwartz argues, is not just the Depression; it is the processes of Americanization reshaping both photography and politics in the 1930s. Historicizing documentary, this book reimagines Evans and his legacy—the complexities of claiming “no politics.”

[Walker Evans] is a timely and insightful analysis of documentary photography through the complexities of Walker Evans’ refusal to work politically. Schwartz illuminates numerous aspects of Evans’ life and practice, including detailed studies of certain of his photobooks. In an era in which questions of representation and ‘making history’ are fundamental to our understanding of the world around us, this book is essential reading.

[Walker Evans] succeeds in reconsidering the work and legacy of Evans within a vast constellation of photographers and writers. It is a rich and nuanced work for students of American photography and documentary made during the twentieth century, especially those interested in politics and material history. In a time when everything is politics, the search for apolitical action is a particularly helpful tool for interrogating our own ideas about the topic.

[Schwartz] takes an approach that honors Evans’s own attitude toward photography: 'a mode of work in which refusing politics was the only way to work politically'...Plentiful black-and-white photographs are placed to maximize Schwartz’s argument, using Evans’s own words. Although Evans scholarship is a crowded field, Schwartz’s book offers a thoughtful perspective on a complicated artist. Recommended.

Schwartz does not construct her own Walker to analyse...but focusses more directly on his work itself. In a way, she looks closely at a thick visual slice of him instead of trying to digest his complex self as a whole...Schwartz challenges the reader with detailed studies of some of [Evans'] photobooks as well as modern photography’s most canonical texts. These raise issues of representation and, more critically, how documentaries serve to create history via visual narration.

There has been a great deal of writing on American documentary in general and Walker Evans in particular, but Stephanie Schwartz's Walker Evans: No Politics is in a class of its own. Schwartz thinks with, or alongside, Evans to interrogate documentary as a key modernist practice, always collaborative and compelled to historicize. In her hands, documentary emerges from the prison house of the Depression to address our future. This is the best work of photographic history to appear in a long time.

Walker Evans continues to be a uniquely resonant emblem of our modernity, a quivering symptom of what has been variously called Americanization, globalization, and neoliberalization. Stephanie Schwartz delves deeply into Evans's portrayal of the thrilling and terrifying conflation of public and private life that has quickened this transformation. In so doing she invites us to consider an altogether different account of documentary photography and, even more so, the root meaning of what it has documented. Highly recommended.

This book is nominally about Walker Evans's strategies and also about the unimagined portions of human existence still waiting for recognition. Stephanie Schwartz asks us to step back from the clichés that have grown up around documentary photography in the years since Evans began. She rereads some of modern photography's most canonical texts and sharpens the facts in the empirical record. She explodes the time zones of the news. The result refocuses some of our most pressing questions as we seek to understand what the sight of another person might actually mean.

- Introduction: Refusals

- Part I. American Histories

- Collaboration

- Doing Anything for Work

- Too Much Time

- Inconsolable Memories

- Part II. Late Portraits

- Taking Credit

- History Lessons

- Persons and Publics

- Nothing to See Here

- Part III. Yesterday’s News

- A Dream Job

- Tabloid Time

- American Holiday

- Domestic Screens

- Coda: Remakes

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index