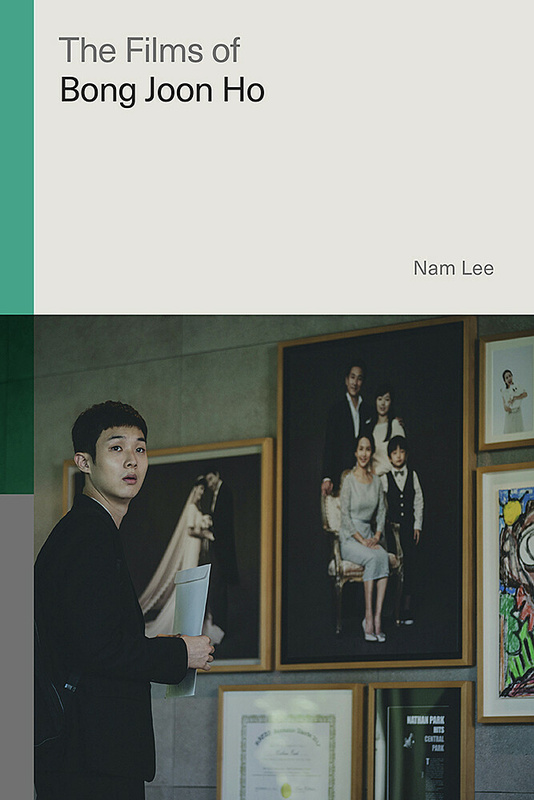

Bong Joon Ho won the Oscar® for Best Director for Parasite (2019), which also won Best Picture, the first foreign film to do so, and two other Academy Awards. Parasite was the first Korean film to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes. These achievements mark a new career peak for the director, who first achieved wide international acclaim with 2006’s monster movie The Host and whose forays into English-language film with Snowpiercer (2013) and Okja (2017) brought him further recognition.

As this timely book reveals, even as Bong Joon Ho has emerged as an internationally known director, his films still engage with distinctly Korean social and political contexts that may elude many Western viewers. The Films of Bong Joon Ho demonstrates how he hybridizes Hollywood conventions with local realities in order to create a cinema that foregrounds the absurd cultural anomie Koreans have experienced in tandem with their rapid economic development. Film critic and scholar Nam Lee explores how Bong subverts the structures of the genres he works within, from the crime thriller to the sci-fi film, in order to be truthful to Korean realities that often deny the reassurances of the happy Hollywood ending. With detailed readings of Bong’s films from Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000) through Parasite (2019), the book will give readers a new appreciation of this world-class cinematic talent.

For the legions of new fans of Bong Joon Ho, this timely book will demonstrate that the triumph of Parasite in the West was no fluke. Nam Lee demonstrates in loving detail just how Bong has managed over a two decade-long career of unprecedented critical and commercial success to condemn and critique contemporary society through the lens of satire, humor and sheer entertainment. It’s hard to think of a director better able to address both Korean controversies and universal anxieties and a writer better able to explicate these concerns.

The Films of Bong Joon Ho is at once a path-breaking study of the director Bong Joon Ho—one of the most recognized and internationally acclaimed filmmakers currently active in South Korea—and his films and simultaneously a study of how the post-1987 South Korean film industry came into being. Drawing upon her own rich experience as a former staff writer and film critic in South Korea and with judicious use of relevant critical theories, Lee offers us both the larger sociopolitical, historical, and cultural context of Bong’s films as well as detailed analyses of a set of films, both critically received and commercially successful ones as well as relatively unknown earlier short films. This book is a great service not only to the fans of Bong but also to the general public who are interested in films of South Korea, as well as to the scholarly community of film studies and Korean studies.

For the legions of new fans of Bong Joon Ho, this timely book will demonstrate that the triumph of Parasite in the West was no fluke. Nam Lee demonstrates in loving detail just how Bong has managed over a two decade-long career of unprecedented critical and commercial success to condemn and critique contemporary society through the lens of satire, humor and sheer entertainment. It’s hard to think of a director better able to address both Korean controversies and universal anxieties and a writer better able to explicate these concerns.

The Films of Bong Joon Ho is at once a path-breaking study of the director Bong Joon Ho—one of the most recognized and internationally acclaimed filmmakers currently active in South Korea—and his films and simultaneously a study of how the post-1987 South Korean film industry came into being. Drawing upon her own rich experience as a former staff writer and film critic in South Korea and with judicious use of relevant critical theories, Lee offers us both the larger sociopolitical, historical, and cultural context of Bong’s films as well as detailed analyses of a set of films, both critically received and commercially successful ones as well as relatively unknown earlier short films. This book is a great service not only to the fans of Bong but also to the general public who are interested in films of South Korea, as well as to the scholarly community of film studies and Korean studies.

When Bong Joon-ho announced a monster movie, The Host, as his new project in 2004, many if not all Korean film industry insiders were skeptical, despite Bong’s great success—both critical and commercial—with his feature film Memories of Murder the year before. Nobody could predict the record-breaking blockbuster phenomenon the film was to become in 2006. Upon its release on July 27, the film broke the opening-day record; set a new domestic record by surpassing the 10-million-ticket-sold threshold in just 21days[1]; and became the highest grossing film of all time with over 13 million tickets sold. It maintained this record for the next eight years. The Host was successful not only domestically but also internationally: It screened at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival to critical acclaim and earned Bong international recognition.[2]

The reason this project initially met with strong skepticism was, in large part, because monster movies have never before been popular with Korean audiences. Unlike Japanese cinema, which has established a unique kaiju (strange beast) genre, South Korean cinema does not have a strong monster genre tradition. The 1960s especially saw a few notable kaiju-influenced films, but for the most part, they were considered children’s movies and were not taken seriously; moreover, their special effects were poor.[3] Thus, Bong’s plan to make a monster movie that required significant use of sophisticated visual effects was considered reckless, and some tried to dissuade him from attempting the project.

Of course, skepticism about his film projects was nothing new to Bong Joon-ho. In fact, industry insiders had scornfully predicted that his first three feature films would be disasters. The story told in his debut film, Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), of dogs that go missing in a small apartment complex, was deemed too trivial for a feature film, and Memories of Murder (2003) was scorned as commercial suicide because it was a crime thriller in which detectives fail to capture the killer. At the time, the Korean domestic film market was dominated by romantic comedies with happy endings, so Bong was advised to change the film’s ending so the mystery was solved satisfactorily. However, Bong kept the original conclusion because it was based on an actual unsolved serial murder case and he wanted to remain true to the real story. Some investors even pulled out after seeing the edited film. Bong was an unknown young director at the time, but he could make these films as he had originally conceived of them because of the unusual support he received from his producer.[4]

The fact that, from the outset of his career, Bong has maintained the original conception of his films against all odds is crucial to understanding his approach to filmmaking. Although he makes mainstream commercial films, he does not abide by the accepted rules or conventions of established genres. He has always been a self-conscious auteur who refuses to compromise his own vision and integrity as a filmmaker. Instead, he tweaks, turns, and inverts conventions and even turns them upside down. Still, he completely snubs skepticism that clouded his new projects every time and pulls off great box-office successes and critical acclaim. In his films, the guilty gets away with murder, literally and/or figuratively. His genre films—whether a crime thriller, monster movie, or science fiction—do not give audiences the reassurance offered by their Hollywood counterparts. Rather, his films usually end without a clear sense of resolution, leaving the audience puzzled, if not bewildered. The absence of the Hollywood “happy ending” constitutes one of the most prominent elements of genre subversion in Bong’s films: the dog killer gets away in Barking Dogs Never Bite; the detectives fail to capture the serial killer in Memories of Murder; the family cannot save their daughter from the monster in The Host; the real murderers are set free in Mother (2009); the world comes to a bleak end in Snowpiercer (2013); the girl saves her giant pig, but the horror of the slaughter house continues in Okja (2017); and all four members of the poor family succeeds in getting jobs with the wealthy family but their successful scheme only leads to a total catastrophe in Parasite (2019).

Even so, Bong’s films are immensely popular among Korean audiences, and with the success of his global projects Snowpiercer and Okja followed by Parasite receiving the Palm d’Or at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, he has become the most widely known and sought-after Korean director on global stage as well. Bong’s unique achievement as a filmmaker lies in his successful foray into what I would describe as “political blockbuster” filmmaking. The “political” in his films is not overt or didactic but effortlessly blends into the pleasures of entertainment films. Instead, the films are political in their aesthetics of subverting the conventions of blockbuster films, and in the sense that they draw our attention to the world we live in and encourages us to ponder the social and political issues we identify with in his films. In certain ways, his films provide a cultural forum where important and pressing social issues are mobilized and discussed by the audience. For example, Okja prompted online discussion about the modern meat industry, and, as the website foodbeat.com reported in July 2017, inspired some people to go vegan.[5] Similarly, as will be discussed in detail in Chapter 5, Snowpiercer opened up a public discussions on issue of global warming. Parasite, which became Bong’s second film after The Host (2006) to surpass 10 million ticket sales in Korea, saw a proliferation of interpretations of the various symbols in the film mostly focusing on the issue of class polarization in Korean society.

Whether set in South Korea (hereafter, Korea) or in an imaginary space, the stories in Bong’s films are grounded in realities of the world and address issues that affect everyday lives. And these stories are always told from the perspective of ordinary people. Indeed, Bong’s films pay particular attention to the socially weak. The protagonists of his films are unlikely heroes—a dim-witted father in The Host, a poor middle-aged single mother and her mentally disabled son in Mother, a young girl from rural Korea in Okja—who are thrown into situations in which they have to battle against power (whether political or corporate) in order to save their loved ones. And it is the plight of the socially weak that seems to resonate with the audiences both locally and globally.

Leitmotif of Misrecognition

With seven feature films between his debut in 2000 and 2018, Bong has established himself as a rare film director who garners both critical acclaim and commercial success while maintaining full control over his work. He has successfully balanced entertainment and social commentary, as the issues embedded in the stories do not overshadow the cinematic enjoyment they provide. Bong achieves this by cleverly using the leitmotif of “misrecognition” or “misconception”—an inability to recognize an object or a person, mistaking it for another, or holding inaccurate expectations about it—that functions as the main trigger of the narrative. This is the most consistently repeated theme found in his films and is most evident in his thrillers, a genre that lends itself to this theme through the mystery-based structure in which the protagonist is often chasing an unknown criminal. Thus, in Bong’s thrillers, protagonists often fail to recognize the criminal or perceives the wrong person to be the criminal. As a result, they fails to capture the culprit.

In Barking Dogs Never Bite, the protagonist, desperate to stop a neighbor’s dog from barking, kidnaps and hides it in the basement of his apartment building, only to learn that he has stolen the wrong dog. Before he can release it, however, the building’s janitor kills and cooks the dog; thus, this initial misrecognition triggers the film’s horror subplot. The plot of Memories of Murder is a series of one misrecognition after another, and the primary question the narrative raises—who is the serial killer preying on the young women of this rural village?—is never answered. A young girl is captured by the river monster in The Host only because her father, running away from the monster, grabs the hand of another girl, leaving his daughter behind to be snatched away by the monster’s tail. Moreover, the characters in The Hostnever learn what has created this monster, although its origins are revealed to the audience in the film’s prologue.

Mother is the story of a woman trying to prove her son’s innocence when he is charged with murder, and this murder charge is the misconception that sets the story in motion. The mother mistakes two other men as the real killer before learning she is the one who has been laboring under a misconception all along; rather than the innocent victim she believes him to be, her son is, in fact, the murderer. At the same time, detectives misread blood found on another boy’s shirt as proof of his guilt and charge him with the murder in the film’s final misrecognition.

The very premise on which the story of Snowpiercer is built is a misconception. In this film, the remnants of the world’s humanity circle the earth in a perpetually running train, believing the ice age blighting the planet has made it uninhabitable. At the film’s end, however, this belief is revealed to be false as, following a revolt within the train during which an explosion derails it and frees its inhabitants, the survivors of the crash venture out, possibly to start human civilization anew. An earlier misconception is revealed when the leader of the revolt confronts the train’s owner and operator, only to learn that the train is run not by mechanics alone but is dependent on child labor.

In Okja, the protagonist Mija’s mission of saving her super-pig Okja begins when it is taken away by the Mirando Corporation that genetically engineers super-pigs for food consumption. Mija was unaware of the fact that Okja was an engineered pig and that she is to be taken away to the US by the Mirando Corporation for the final leg of the super-pig competition. Thus, when Dr. Johnny, the ambassador of the Mirando Corporation, and his filming crew arrives at her house, she misrecognizes him as the famous TV personality filming an episode in her house. That is why she follows her grandfather without any suspicion to leave the house to the filming crew and visit her parents’ grave. Also, one of the climactic scenes in the film rests on an intentional mistranslation. After the Animal Liberation Front has helped Mija to reunite with Okja, the ALF leader Jay wants to ask Mija if she will agree to their next mission to take Okja to New York to penetrate the Mirando Corporation to take them down from the inside. If she does not agree, they will not pursue their mission. The Korean-American member K acts as an interpreter between them. Mija replies that she does not agree and she just wants to take Okja back to the mountain. At this critical moment, however, K decided to give a deliberate mistranslation and tells the ALF members she agrees. This triggers the narrative forward to New York and subsequently the slaughter house. Thus, Okja’s narrative is built upon three misunderstandings or misrecognition: first, that Mija thought Okja was a pet she can keep forever; second, she misrecognized Dr. Johnny to be just the famous TV personality; and lastly, she did not even know that her answer is mistranslated and that is why they are going to New York.

Parasite takes this motive of “misrecognition” to a new level. While the misrecognitions in the previous films were not intentional ones, it is actively pursued by the protagonists in this film. The four members of the poor family succeeds in getting hired by the rich family all by pretending to be somebody else, presenting false identity and resume. They also pretend to be strangers to one another. The whole film is triggered by their pretentions. (The film even has a scene in which the son Kiwoo asks Dahye whom he is tutoring to compose an English paragraph using the word “pretend” at least two times).

Alfred Hitchcock is the greatest master of the wrong-man/wronged-man motif, and the plots of his films are often structured on misrecognition. Bong effectively appropriates Hitchcock’s motif of misrecognition to express the absurdities of the Korean realities and global issues. In Barking Dogs Never Bite, Memories of Murder and Mother, characters are wrongfully accused or convicted of crimes; however, unlike various Hitchcockian protagonists wrongfully identified, pursued, and—in the case of The Wrong Man (1956)—charged with a crime, Bong’s characters are often not cleared or set free, or at least not until after having experienced violence or torture. Further, Bong’s narrative structures are more complex than Hitchcock’s. For instance, Mother has dual narrative strands consisting of two murders committed by two separate individuals; moreover, both murderers go free while the audience knows—although the police in the film do not—a wrongfully convicted man remains in prison. The complexity of this dual structure, and the layering of mismatched knowledge, is more effective than a straightforward mystery in conveying the peculiar realities of Korean society. Bong uses the leitmotif of “misrecognition” because, it seems, it provides the most effective tool to reveal the social absurdities of contemporary Korean society. Korean citizens (including the characters in his films) expect that the system that governs the nation will protect and save them from disasters or crisis but their expectations are always betrayed.

Indeed, Bong’s first four films and Parasite, set in Korea capture Bong’s idea of “Koreanness.” Before expanding his filmmaking to a global level with Snowpiercer and Okja, his aim was to appeal exclusively to the Korean audience. He has stated that The Host, which enjoyed international success, “was acclaimed at Cannes but they do not understand this film 100%. The film is full of humor and comedy only Koreans can understand.”[6] But he added, that he was “happy to see that Korean sentiment and sensibilities also worked in the West.”[7] Specifically, Bong localizes “conventional” (i.e. Hollywood) genres within Korean stories, realities, and sensibilities. And it is this localization that makes the subversion of genre conventions inevitable as Chapter 3 will demonstrate. Unlike Americans whose collective trust and belief in their governmental system and authority is usually reflected in Hollywood films, Koreans generally are suspicious of their government or authorities. And these two opposing tendencies or sensibilities clash within Bong’s films to create his unique adaptation of Hollywood genres.

“Koreanness” as Social Absurdities

The notion of “Koreanness” can be interpreted in different ways. So how, precisely, does Bong define the “Koreanness” that informs his filmmaking? For Bong, “Koreanness” does not lie in the traditional Korean culture of the pre-modern era. In this, he differs from veteran director Im Kwon-Taek, whose films are often associated with the uniquely Korean notion of “han.” This is a concept which has no English equivalent but which refers to unresolved grief, grudges, or regrets, a sentiment that has accumulated in the hearts of Koreans throughout the country’s tumultuous history. In contrast, in Bong’s films, “Koreanness” lies, in his own words, in the “absurdities” or “irrationalities” (“bujori”)[8] of everyday life. In his films, the social bujoris are the result of the widespread political corruption, social injustices, and anomie of contemporary Korean society, and these bujoris are the key to understanding Bong’s films. For instance, these bujoris are the reason his films lack clear resolutions. They also account for his films having narratives that result in failure.

This element, which I call the “narrative of failure,” can be explained by Korea’s discourse of “failed history.” Specifically, after liberation from thirty-six years of Japanese colonial rule in 1945, Korea experienced postwar US occupation, national division, civil war (i.e., the Korean War), and then almost three decades of successive military dictatorships that came to an end only in the late 1980s after an intense struggle for democracy. However, pride in achieving democracy turned into increasing confusion and cynicism after a financial crisis in 1997 and an IMF bailout that mandated the adoption of neoliberal measures, which, in turn, intensified the economic inequalities and social injustices.

One cause of the persistent social injustices and political corruption in Korean society can be traced to Korea’s failure to identify and prosecute collaborators and perpetrators of Japanese Imperialism and the military dictatorships, particularly those involved in the Kwangju Massacre in May 1980, during which Korean paratroopers turned their weapons on civilian protesters demanding democracy. Even after democratization in 1987, no substantial change has been achieved in Korea’s system of corruption and bujoris. Thus, today a sense of despair, anger, and cynicism is widespread in Korea. Man-made disasters occur frequently and the government and other authorities often fail to protect ordinary citizens; these are the historically accumulated sentiments that Bong’s films capture and which strike a chord with Korean audiences.

Bong’s observations on the workings of Korean society are so keen and accurate as to be almost prophetic. In his 2006 blockbuster The Host, a monster emerges from the Han River and attacks people along the shore. However, government authorities in the film are bent on chasing a family victimized by the monster rather than on containing or killing it. Furthermore, the authorities continue to pursue the family as carriers of a monster-borne virus even after learning that the virus does not exist.

Six years after its release, the film was summoned back to public discourse in the aftermath of the worst ferry disaster in history. On the morning of April 16, 2014, the ferry Sewol capsized and sank off Korea’s south coast, killing 304 people. The victims were mostly high school students on their way to Jeju Island for a school excursion. The nation watched the Sewol sink in real time on live TV broadcasts as government rescue efforts failed to arrive in time to save the passengers. Most viewers identified with the horror the students’ parents must have felt as they watched helplessly, unable to save their children. President Park Geun-hye was conspicuously absent while the boat was sinking; it was revealed later that poor oversight by regulatory bodies had contributed to the disaster, and the government was accused of a cover-up. The victims’ families and other members of the public engaged in protests, but the government refused to investigate and has never explained why rescue services were late in responding to the disaster. Further, instead of investigating what went wrong, the government began to accuse the protesting families of politicizing the event, going so far as to label them North Korean sympathizers bent on disrupting the current political system.

The striking similarity between the Sewol ferry disaster and the monster attack in The Host became an immediate topic of discussion on social media, as reflected in these sample posts: “Is Bong Joon-ho’s film The Host a prelude to the Sewol Disaster? The nation’s incompetence, the families’, especially the father’s, desperate struggle, and the victimized young child. It seems that the fathers’ desperate struggle will continue in this monsterized society” (twitter id @tell65, Aug 22, 2014); “Watching Bong Joon-ho’s The Host again and this is completely identical. Director Bong’s incredible insight” (twitter id @hanjovi21, July 15, 2014). The comic writer Lee Jae-suk wrote, “On second viewing, [The Host] is a film about Korea and Sewol disaster…Bong Joon-ho’s The Host is not an SF fantasy film” (twitter id @kkomsu10000 July 5, 2014). This evocation of The Host in the wake of the Sewol ferry disaster is a testament to the extent to which Bong’s films provide a keen insight into contemporary Korean society. His films are in a way a study of the social ills and their effect on the lives of ordinary Korean people.

Therefore, his films can be best understood through an examination of the Korean realities that serve as their subtexts. Specifically, the chronotope[9] of his films is the transitional period in Korean history between the military dictatorship of the 1980s and the democracy and neoliberal capitalism of the twenty-first century. His films probe the dire consequences of the rapid economic growth Korean society experienced in the forty years after the Korean War (1950-1953), known as the “economic miracle,” during which Korea transformed itself from one of the world’s poorest nations to one of the world’s largest economies. Politically, Korea transitioned within twenty-six years from a military dictatorship in 1961 to a democratic society in 1987. In economic terms, the transition from military dictatorship to a democratic society was a journey from state-planned economic growth to neoliberal capitalism.

While Memories of Murder looks back at the dark era of the 1980s military dictatorship, Barking Dogs Never Bite, The Host, and Mother dig beneath Korea’s postwar economic miracle and explore the ways in which its consequences drove individuals, especially the socially weak, into disastrous situations. Bong interrogates the superficiality of the parliamentary democracy and reveals how the pre-existing system of social ills and corruption has been maintained, and has even intensified, in post-democratic Korean society.[10]

Bong stands out among contemporary Korean film directors for his politically and socially conscious approach to filmmaking; perhaps alone among his cohort, he maintains a critical gaze toward Korean society while also making popular films. His work explores the problems of Korea’s social system, reveals political and moral corruption and social injustice, and (in)directly addresses unresolved issues in Korean history. Uniquely, however, his work remains squarely in the realm of commercial entertainment, achieving wide appeal through his appropriation of Hollywood genres. Thus, his films differ from those of other well-known and critically acclaimed Korean directors such as Lee Chang-dong, Hong Sang-soo, and Kim Ki-duk, whose film styles are more radical and whose works circulate mostly in the art cinema/film festival circuit.

At the same time, Bong is also different from Park Chan-wook, who also works within a genre tradition. While Park’s films manifest auteur-consciousness through their excessive stylization, Bong’s films are more realistic, both visually and thematically. They are also more mass-oriented than Park’s, with playful subversions of genre conventions and blockbuster spectacles, whereas Park’s films tend to be more serious and philosophical, with twisted stories that unfold around the theme of revenge. Bong’s films are more sociological than philosophical. However, this does not mean Bong is not conscious of being an auteur. Rather, he strongly defends his integrity as an auteur to such a degree that he is willing to risk commercial success to maintain full control over his work, as his struggle with Harvey Weinstein over the U.S. release of Snowpiercer demonstrates.[11] Rather than conforming to the distributor’s request to cut twenty minutes of his film to guarantee a wider release, Bong opted for the limited release of the uncut version. This decision reinforces the idea that Bong often goes against suggestions for wider audiences; instead he pushes forward his original vision for his films. Despite his decision to go to limited release, Snowpiercer became one of the most watched of his films in the US through streaming service, which in turn, led the distribution company to increase the number of screens in the theaters.

Bong’s international success offers an interesting case study of making films that are at once nationally specific and universally appealing. It is fair to say that this transnational appeal of his films is related to the economic globalization and the spread of neoliberal capitalism worldwide. Since the late 1990s, Korea has been at the forefront of neoliberal capitalism and Bong’s films capture the various social ills intensified by the neoliberal policies of deregulation of government measures to control markets, privatization of public assets, cutback of social welfare, and de-unionization, all of which engender corporate greed and widen the gap between the rich and the poor. As these neoliberal measures spread with the global market economy, the consequences are shared globally as well. Thus, although Bong’s films portray specifically Korean realities, the underlying social problems and issues are universal. As he ventured into English-language global filmmaking with Snowpiercer and Okja, his scope of social inquiries also expanded to include global issues. These two films are global versions of his Korean language films in terms of their interrogation of social systems and their biting critique of neoliberal capitalism. Snowpiercer is an allegory of the ever-widening gap between the rich and poor while raising the global issue of climate change; Okja deals more directly with corporate greed and the issues of genetically modified food and the cruelty of animal factory farms.

By combining Hollywood genres and local politics, Bong opens up what Homi Bhabha terms a “Third Space” [12]of enunciation in which the cultural differences between postcolonial society and the West are translated and articulated. Bhabha posits that recognition of this Third Space opens the way to “conceptualizing an international culture, based not on the exoticism or multiculturalism of the diversity of cultures, but on the inscription and articulation of culture’s hybridity.” Bong Joon-ho’s films can be considered as the product of this hybrid filmmaking, standing as he does between Hollywood filmmaking on one hand and Koreanness on the other. The contemporary Koreanness in his films is rooted in the various historical, social, political and cultural abnormalities Korea is faced with as a postcolonial society. By bringing together elements from each, he creates something new and uniquely his own.

However, it is not the goal of this book to trace the uniqueness of Bong’s films solely to his cinematic genius or to link them to the romantic notion of an auteur whose intentions provide the keys to understanding the meaning of his films. Rather, the book takes the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s idea that a work of art is not a product of some sort of inspiration from, but a social phenomenon shaped by concrete social and historical process. Bourdieu’s concept of a “field of cultural production,” the idea that understanding a work of art involves not only looking at the art itself but also the conditions of its production and reception, provides a tool to overcome the opposing approaches to studying work of art: the internalist approach that focuses on the work’s formal qualities and structural determinism that claims that art is a mere reflection of social structures.[13] His claim that “scientific analysis of the social conditions of the production and reception of a work of art, far from reducing it or destroying it, in fact intensifies the literary experience”[14] supports the aim of this book to provide concrete historical, social and cultural context—the field of production—to enhance the pleasure of discovering the rich subtext in Bong’s films. While recognizing his creative agency, the book acknowledges that all forms of culture, including films, are shaped by social practices and that the creators are also cultural products.

Bong Joon-ho himself can be described as a “cinematic sociologist” whose films are embedded in concrete social realties of both Korean society and neoliberal capitalism at large. His films are about individual lives—in particular, the marginalized of the Korean society. However, they are always positioned within the larger social, political, and economic context. In this sense, his films realize what American sociologist C. Wright Mills termed as “sociological imagination,” a creative way of understanding the private troubles by looking at them within larger social realities and public issues.[15]All of his films are about the plight of ordinary people, the disadvantaged, and in the process of portraying the difficulties they face, his films reveal and suggest to the audience the root cause of their predicaments. This will be analyzed in detail in the subsequent chapters; however, for example, Memories of Murder places the serial murderer and the incompetent police within the larger context of the 1980s military dictatorship; in The Host, the root causes of the tragedy of the Park family are the postcolonial conditions of Korea: its subservient relationship to the U.S. and the corrupt authorities. The moral corruption of the protagonists in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Mother are not depicted as caused by individual’s monstrous nature but rather by the harsh social and economic conditions forced upon the weak. In Snowpiercer and Okja, Bong’s cinematic sociology become more overtly political to indict the global phenomenon of neoliberal capitalism that allows corporate greed to disregard dire issues of global warming and animal cruelty. Parasite brings a renewed attention to the issue of class, the polarization of the rich and the poor under neoliberal capitalist society in which upward mobility is no longer attainable for those who have fallen through the cracks.

Thus, the chapters of this book are structured thematically in terms of the Korean context of the specific social ills and corruption the aforementioned leitmotif of “misrecognition” and “misconception” aims to reveal.

Chapter 1, A New Cultural Generation provides a brief biography of Bong Joon-ho, summarizing the diverse and hybrid cultural influences on his work. It analyzes his short films and the films he worked on as a screenwriter before becoming a director. With this background, the chapter then positions Bong Joon-ho and his films within the context of New Korean Cinema. Characterized by the emergence of cinephile filmmakers and audiences, the New Korean Cinema burst onto international movie screens at the new millennium. Among the most popular and influential of these millennial films, which demonstrate Korea’s powerful pop-culture presence, were Shiri (1999), JSA (2000), My Sassy Girl (2001), and Oldboy (2003). Of all these films, however, the most popular by far was The Host (2006). A record-breaking blockbuster in Korea, the film also achieved acclaim internationally with serious movie fans and cult audiences alike.

Chapter 2, Cinematic “Perversions”: Tonal Shifts, Visual Gags and Techniques of De-familiarization focuses on Bong’s formal techniques and visual expression. It closely examines how Bong’s focus on “Koreanness” is communicated visually and formally. Specifically, I discuss Bong’s major filmic techniques of genre bending and tonal blending; his realist aesthetics, analogous to the tradition of the “real-view landscape” in Korean painting; and his de-familiarization of everyday spaces. I borrow the Russian formalist literary critic Viktor Shklovsky’s notion of “de-familiarization”—making familiar objects appear unusual or new to the viewer/reader—to explain Bong’s use of space in his films. Bong tends to use spaces that are often overlooked, such as the basement of an ordinary apartment in Barking Dogs Never Bite,and the sewage of the Han River in The Host. His films turn these everyday spaces into spaces of horror. The real-view landscape painting is wonderfully referenced or recreated in Memories of Murder and Mother, films that are set in Korea’s rural area.

Chapter 3, Social Bujoris and the “Narratives of Failure”: Transnational Genre and Local Politics in Memories of Murder and The Host, focuses on and analyzes the ways in which Bong utilizes specifically Korean politics in the narratives of the crime movie (Memories of Murder) and the monster movie (The Host) to subvert and re-invent genre conventions. Bong has shaped these films with specifically Korean narrative forms I identify as “narratives of failure.” These “narratives of failure” reflect the self-perception of “failed history” that characterizes the collective experience of Korean society since the mid-twentieth century, beginning with its liberation from three decades of Japanese colonial rule in 1945 and concluding with the neoliberal capitalism of the twenty-first century. Both films position the 1980s as the crucial transitional period in Korea’s postwar history that created Korean society as it exists today.

Chapter 4, Monsters Within: Moral Ambiguities Anomie in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Mother, explores these films’ representation of the social effects of South Korea’s experience of compressed economic growth. The rapid economic growth the nation experienced following the Korean War transformed Korea, in a matter of decades, into an urban, industrialized nation, bringing about great social confusion and disruption of moral values. Both films portray the emotional struggle ordinary Koreans faced, with moral dilemmas arising from Korea’s adoption of neoliberal policies in the late 1990s. In these films, the socially weak are not portrayed as mere victims of the system but as driven to succumb to moral corruption by their desperate situations. In these films, the line between good and evil is blurred, and the films illustrate the manner in which moral confusion and anomie has intensified in the lives of the individual as a result of the major political, industrial, and financial shifts Korea has experienced in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Chapter 5, Beyond the Local: Global Politics and Post-apocalyptic Imagination in Snowpiercer and Okja, situates these two films within the context of global filmmaking and illustrates their radical politics by examining first how the train in Snowpiercer and the Mirando Corporation in Okja symbolize a microcosm of the current neoliberal capitalist system, and, second, how the films’ transnational appeal can be located in the global expansion of this neoliberalism. The films create what Nancy Fraser has termed a “new political space” to raise issues of global injustice and inequality, as well as environmental issues. The radical politics of the tail section’s revolt are in Snowpiercer is analyzed in terms of Jacque Rancière’s redefinition of politics and his notion of the “distribution of the sensible,” and Okja is analyzed in terms of the relationship between film and activism focusing on the fact that Okja initiated among its audience a movement to go vegan.

Chapter 5 is followed by Conclusion and a detailed Filmography of all Bong Joon-ho films. The analysis of his latest film Parasite offers a wonderfully fitting conclusion to the book as it is at once Bong’s return to Korean realities and a departure to a new level of his idiosyncratic approaches to genre filmmaking. The film summons his previous films in various ways but at the same time departs from them in its focus on sociological aspects of emotion which has been considered as something individual and personal. The film shows how the feelings of humiliation is built up in the poor and the deprived in contemporary Korean society and how it can trigger a total catastrophe in which nobody is a winner. Filmography includes short and feature-length films he directed as well as those he did not direct but produced, wrote or acted in. The detailed synopsis of each film will allow those readers not familiar with all of Bong’s films to obtain necessary information to help follow the analysis of each film in this book.

By grounding the films of Bong Joon-ho securely within the sociopolitical transformation of South Korean society since democratization in 1987 and global expansion of neoliberal capitalism in the 21st century, this book aims to illustrate the ways in which his films are reflections of a growing sense of injustice and failure among South Koreans in the age of neoliberal globalization, a sentiment global audiences identify with as well. Films cannot be isolated from the cultural system that generated them. Placing Bong’s films in the dual context of the transition from military dictatorship to democracy in Korean history and the simultaneous changes in the Korean film industry will clarify to the non-Korean readers the rich Korean subtext crucial to a full understanding of the films of Bong Joon-ho.

Notes to Introduction

ebook.

List of Illustrations

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1 A New Cultural Generation

Chapter 2 Cinematic “Perversions”: Tonal Shifts, Visual Gags and Techniques of Defamiliarization Chapter 3 Social Pujoris and the “Narratives of Failure”: Transnational Genre and Local Politics in Memories of Murder and The Host

Chapter 4 Monsters Within: Moral Ambiguity and Anomie in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Mother

Chapter 5 Beyond the Local: Global Politics and Neoliberal Capitalism in Snowpiercer and Okja

Conclusion: Parasite, A New Beginning?

Filmography

Bibliography

Index