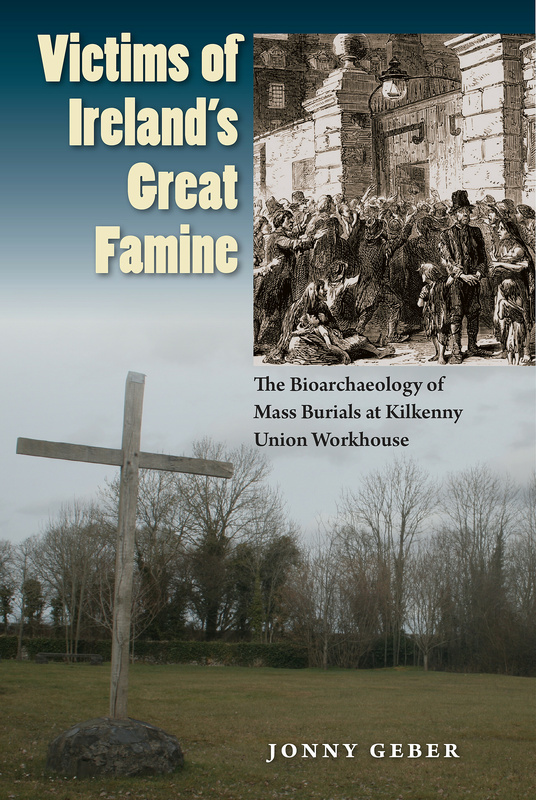

Victims of Ireland's Great Famine

The Bioarchaeology of Mass Burials at Kilkenny Union Workhouse

“Sets Irish archaeology on an exciting new course by tangibly proving the harshness of the famine and the workhouse system.”–Charles E. Orser Jr., author of The Archaeology of Race and Racialization in Historic America

“Sheds critical new light on the actualities of daily life in Famine-era Ireland, challenges some of the myths about the horrors of the workhouse experience, and restores humanity to the nameless dead.”–Audrey Horning, author of Ireland in the Virginian Sea: Colonialism in the British Atlantic

With one million dead, and just as many forced to emigrate, the Irish Famine (1845–52) is among the worst health calamities in history. Because historical records of the Victorian period in Ireland were generally written by the middle and upper classes, relatively little has been known about those who suffered the most, the poor and destitute. But in 2006, archaeologists excavated an until then completely unknown intramural mass burial containing the remains of nearly 1,000 Kilkenny Union Workhouse inmates. In the first bioarchaeological study of Great Famine victims, Jonny Geber uses skeletal analysis to tell the story of how and why the Famine decimated the lowest levels of nineteenth century Irish society.

Seeking help at the workhouse was an act of desperation by people who were severely malnourished and physically exhausted. Overcrowded, it turned into a hotspot of infectious disease–as did many other union workhouses in Ireland during the Famine. Geber reveals how medical officers struggled to keep people alive, as evidenced by cases of amputations but also craniotomies. Still, mortality rates increased and the city cemeteries filled up, until there was eventually no choice but to resort to intramural burials. Deceased inmates were buried in shrouds and coffins–an attempt by the Board of Guardians of the workhouse to maintain a degree of dignity towards these victims. By examining the physical conditions of the inmates that might have contributed to their institutionalization, as well as to the resulting health consequences, Geber sheds new and unprecedented light on Ireland’s Great Hunger.

Shows how archaeology can help both academic and non-specialist readers to comprehend the lives of even the most unfortunate.'–. 'Important and well-conceived. . . . Provides a valuable dataset with which to critically interrogate available historical accounts of the Great Famine, daily life for Ireland's poorer classes, the experiences of being inmates, and conditions within Ireland’s workhouses.'–Journal of Anthropological Research

Jonny Geber is a lecturer in biological anthropology at the University of Otago in New Zealand.