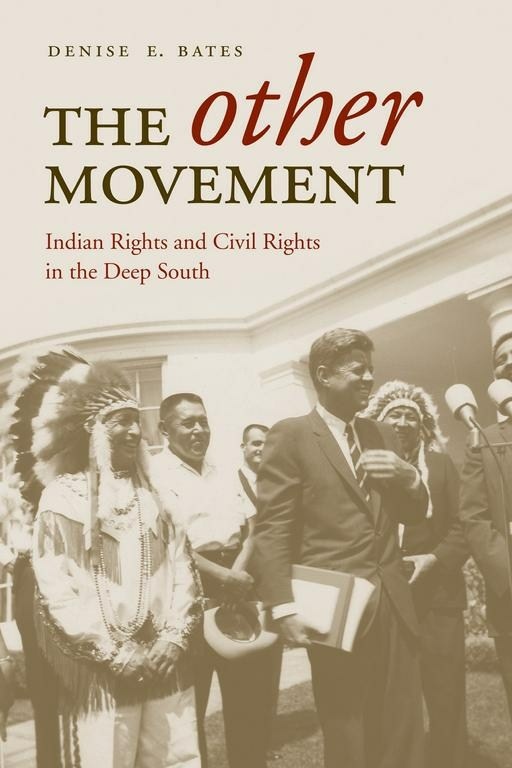

The Other Movement

Indian Rights and Civil Rights in the Deep South

University of Alabama Press

Examines the most visible outcome of the Southern Indian Rights Movement: state Indian affairs commissions

In recalling political activism in the post-World War II South, rarely does one consider the political activities of American Indians as they responded to desegregation, the passing of the Civil Rights Acts, and the restructuring of the American political party system. Native leaders and activists across the South created a social and political movement all their own, which drew public attention to the problems of discrimination, poverty, unemployment, low educational attainment, and poor living conditions in tribal communities.

In recalling political activism in the post-World War II South, rarely does one consider the political activities of American Indians as they responded to desegregation, the passing of the Civil Rights Acts, and the restructuring of the American political party system. Native leaders and activists across the South created a social and political movement all their own, which drew public attention to the problems of discrimination, poverty, unemployment, low educational attainment, and poor living conditions in tribal communities.

While tribal-state relationships have historically been characterized as tense, most southern tribes—particularly non-federally recognized ones—found that Indian affairs commissions offered them a unique position in which to negotiate power. Although individual tribal leaders experienced isolated victories and generated some support through the 1950s and 1960s, the creation of the inter-tribal state commissions in the 1970s and 1980s elevated the movement to a more prominent political level. Through the formalization of tribal-state relationships, Indian communities forged strong networks with local, state, and national agencies while advocating for cultural preservation and revitalization, economic development, and the implementation of community services.

This book looks specifically at Alabama and Louisiana, places of intensive political activity during the civil rights era and increasing Indian visibility and tribal reorganization in the decades that followed. Between 1960 and 1990, U.S. census records show that Alabama’s Indian population swelled by a factor of twelve and Louisiana’s by a factor of five. Thus, in addition to serving as excellent examples of the national trend of a rising Indian population, the two states make interesting case studies because their Indian commissions brought formerly disconnected groups, each with different goals and needs, together for the first time, creating an assortment of alliances and divisions.

Bates’s The Other Movement makes an original and important contribution to the field of American Indian history in the Southeast. In particular, there currently are no published studies detailing the origins of state-tribal relations in Alabama and Louisiana, the administration of state Indian commissions in these states, and inter-tribal politics and conflicts that these bodies often engender. The author does an excellent job using statements of Indian leaders to illuminate issues important to their communities.’

—Mark Edwin Miller, author of Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process

While much attention has been paid to the movement against the injustice of the Jim Crow system in the southern US, Native Americans have complicated the binary racial order in ways that have been systematically erased. In this fine study, Bates highlights the sophisticated ways that Native Americans in Louisiana and Alabama fought to make visible and strengthen their continued existence in the mid- and late-20th century. Her greatest contribution is the way she emphasizes the unique regional history and locates power within two arenas that have been typically contested or dismissed by many federally recognized tribes elsewhere: the state-tribal relationship and the federal recognition process. . . . Bates’s respectful, meticulous analysis makes this a valuable addition to the scholarship on southeastern Native American history. Highly recommended.’

—CHOICE

Denise E. Bates is a historian and lecturer of interdisciplinary and liberal studies in the School of Letters and Sciences at Arizona State University.