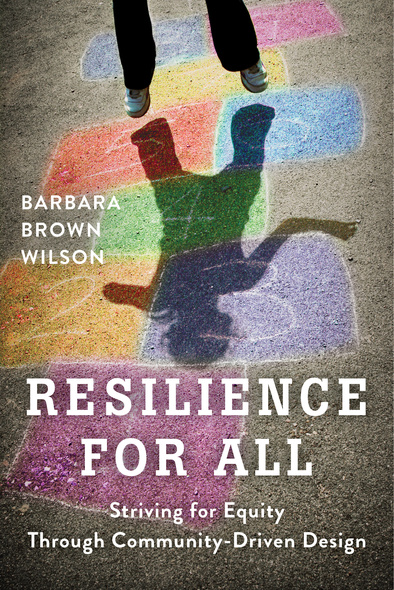

Resilience for All

Striving for Equity Through Community-Driven Design

Island Press

In the United States, people of color are disproportionally more likely to live in environments with poor air quality, in close proximity to toxic waste, and in locations more vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events.

In many vulnerable neighborhoods, structural racism and classism prevent residents from having a seat at the table when decisions are made about their community. In an effort to overcome power imbalances and ensure local knowledge informs decision-making, a new approach to community engagement is essential.

In Resilience for All, Barbara Brown Wilson looks at less conventional, but often more effective methods to make communities more resilient. She takes an in-depth look at what equitable, positive change through community-driven design looks like in four communities—East Biloxi, Mississippi; the Lower East Side of Manhattan; the Denby neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan; and the Cully neighborhood in Portland, Oregon. These vulnerable communities have prevailed in spite of serious urban stressors such as climate change, gentrification, and disinvestment. Wilson looks at how the lessons in the case studies and other examples might more broadly inform future practice. She shows how community-driven design projects in underserved neighborhoods can not only change the built world, but also provide opportunities for residents to build their own capacities.

In many vulnerable neighborhoods, structural racism and classism prevent residents from having a seat at the table when decisions are made about their community. In an effort to overcome power imbalances and ensure local knowledge informs decision-making, a new approach to community engagement is essential.

In Resilience for All, Barbara Brown Wilson looks at less conventional, but often more effective methods to make communities more resilient. She takes an in-depth look at what equitable, positive change through community-driven design looks like in four communities—East Biloxi, Mississippi; the Lower East Side of Manhattan; the Denby neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan; and the Cully neighborhood in Portland, Oregon. These vulnerable communities have prevailed in spite of serious urban stressors such as climate change, gentrification, and disinvestment. Wilson looks at how the lessons in the case studies and other examples might more broadly inform future practice. She shows how community-driven design projects in underserved neighborhoods can not only change the built world, but also provide opportunities for residents to build their own capacities.

Resilience for All is a useful handbook for landscape architects wondering how their skill sets might apply to community-led planning and design. It demonstrates how landscapes can be a powerful resource for vulnerable communities. And it also shows how communities can positively impact landscapes.

Millions of people live in cities but have no say in how they evolve. This results in distortions of the democratic process, which we might call 'planning gerrymandering,' and dysfunctional cities. Resilience for All reports on efforts from around the United States to open up the process, to get the people's voices heard, their power awakened, so that our urbanizing nation can be a healthy one. A great guide for everyone who wants to know the process of better city-making.

This timely book provides the essential documented pathways for dealing with communities of color and distress. In the past, we have spent hours engaging residents at community meetings and invited professional voices to assist us. We assumed we were empowering the community's voice and vision. Resilience for All demonstrates that addressing residents is an initial step, but fully empowering them as the agent of change is the pathway to success.

This book should be required reading for architects, planners, and anyone else working on complex urban challenges. Resilience for All skillfully presents the structural inequities that are the context for public interest design, and offers practical case studies that confront traditional notions of community engagement and the role of the designer. Dr. Wilson connects the dots between systems-level oppression and on-the-ground design interventions that bring new insights and useful methods to today's conversation about equity and ecology in cities. If you read anything about resilience this year, read this book!

Barbara Brown Wilson is an assistant professor of Urban and Environmental Planning and the Director of Inclusion and Equity in the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on the history, theory, ethics, and practice of sustainable community development, and on the role of urban social movements in the built world. Wilson's current research projects include understanding how grassroots community networks reframe public infrastructure in more climate and culturally appropriate ways across the U.S., and helping to elevate the standards of evaluation for community engaged design around notions of social and ecological justice. Her work is often action-oriented, as she collaborates with traditionally marginalized communities to create knowledge that serves both local and practitioner communities. She is author of Resilience for All: Striving for Equity through Community-Driven Design and Questioning Architectural Judgement: The Problem of Codes in the United States.

In Charlottesville, Wilson is supporting three communities through resident-led redevelopment efforts, and helping build programs that prepare resident youth to serve as valued members of the design team for the work in their own communities, and also for future careers in the field. Nationally, she’s been recognized as one of the top 100 leaders in Public Interest Design. She is a co-founder of the Design Futures Student Leadership Forum, a five day student leadership training which convenes students and faculty from a consortium of universities with leading practitioners all working to elevate the educational realms of community engaged design; and a co-founder of the Austin Community Design and Development Center (ACDDC), a nonprofit design center that provides high quality green design and planning services to lower income households and the organizations that serve them.

In Charlottesville, Wilson is supporting three communities through resident-led redevelopment efforts, and helping build programs that prepare resident youth to serve as valued members of the design team for the work in their own communities, and also for future careers in the field. Nationally, she’s been recognized as one of the top 100 leaders in Public Interest Design. She is a co-founder of the Design Futures Student Leadership Forum, a five day student leadership training which convenes students and faculty from a consortium of universities with leading practitioners all working to elevate the educational realms of community engaged design; and a co-founder of the Austin Community Design and Development Center (ACDDC), a nonprofit design center that provides high quality green design and planning services to lower income households and the organizations that serve them.

Preface: On #Charlottesville

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1: Introduction: Resilience or Resistance?

Chapter 2: A Short History of Community-Driven Design

Chapter 3: East Biloxi: Bayou Restoration as Environmental Justice

Vignette #1: Fargo: Playing in the Sandbox in The Fargo Project

Chapter 4: Lower East Side, Manhattan: Tactical Urbanism Holding Space for the People's Waterfront

Vignette #2: San Francisco: Reconsidering Parklets in Ciencia Pública: Agua

Chapter 5: Denby, Detroit: Schools, and Their Students, as Anchors

Vignette #3: The Cochella Valley: Reimagining the Banks of the Salton Sea in the North Shore Productive Public Space Project

Chapter 6: Cully, Portland: Green Infrastructure as an Antipoverty Strategy

Vignette #4: Philadelphia: The “Makerspace” Revisited in The Tiny WPA

Chapter 7: Conclusion: Toward Design Justice

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1: Introduction: Resilience or Resistance?

Chapter 2: A Short History of Community-Driven Design

Chapter 3: East Biloxi: Bayou Restoration as Environmental Justice

Vignette #1: Fargo: Playing in the Sandbox in The Fargo Project

Chapter 4: Lower East Side, Manhattan: Tactical Urbanism Holding Space for the People's Waterfront

Vignette #2: San Francisco: Reconsidering Parklets in Ciencia Pública: Agua

Chapter 5: Denby, Detroit: Schools, and Their Students, as Anchors

Vignette #3: The Cochella Valley: Reimagining the Banks of the Salton Sea in the North Shore Productive Public Space Project

Chapter 6: Cully, Portland: Green Infrastructure as an Antipoverty Strategy

Vignette #4: Philadelphia: The “Makerspace” Revisited in The Tiny WPA

Chapter 7: Conclusion: Toward Design Justice

Notes

Bibliography

Index