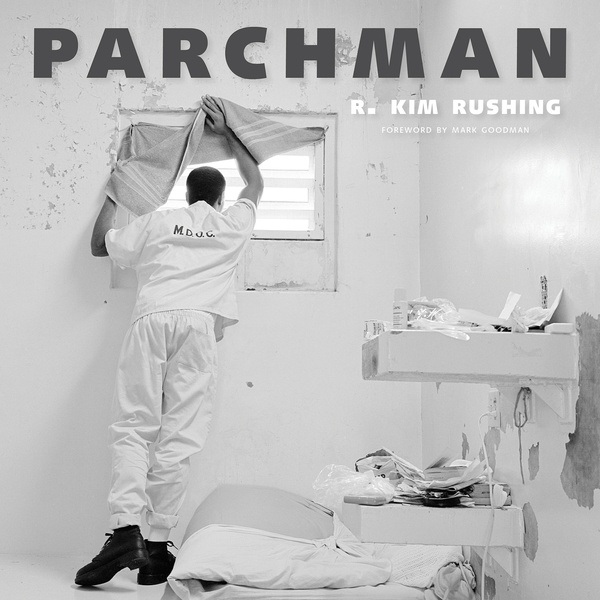

Constructed in 1904, the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman covers 20,000 acres, forty-six square miles, in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. Originally designed like a private plantation without walls or guard towers, the prison farm has been slowly transformed over the decades into a modern penitentiary. In 1994, photographer R. Kim Rushing was the first outside photographer in Parchman’s history allowed long-term access to inmates and the chance to photograph them in their cells and living quarters after earning great trust with his subjects. In Parchman he offers a glimpse of the men incarcerated in this infamous place. Eighteen volunteer inmates, ranging in custody level from trusty to death row, are presented through images and their own handwritten letters.

When Rushing started this work, he brought visceral, human questions. What is it like to be an inmate in Parchman Penitentiary? What happens to an individual there? How does it happen? How do the prisoners feel about their circumstances? What does it feel like when two people from completely different worlds look at each other over the top of a camera?

Moving to Ruleville, Mississippi, a small town in the heart of the Delta, Rushing came face to face with the influence of Parchman State Penitentiary. After becoming known in the area, he was allowed to photograph inmates for almost four years. These men volunteered and permitted him to photograph them in their cells. They even shared their written thoughts about their lives and prison conditions. It is particularly fascinating to see the visible change, or lack thereof, that becomes obvious when viewing portraits separated by two or three years.

These stark, moving portraits of prisoners attest to the impact of photography. The photos are accompanied by the prisoners’ stories, told in their own words. Together the images and words provide the most complete understanding of Parchman ever published.

A study in confrontation: the inmates’ own confrontation of Rushing and the viewer in their portraits, and with their present circumstances and future aspirations through their writing

Thanks to an indulgence—which had never before been granted by the maximum-security state prison in the century of its existence—Kim Rushing separates individuals from the mass of a prison population. There is not an ounce of prurience here. And the shocker is that the scripted words of the respective prisoners become as much of an image of the inmates as are the photographs of the prisoners and their habitats. As we read them, the scripted pages, which are written on all sorts of different papers, acquire stunning character in their own right. And it’s a character and an intimacy sometimes in seeming contrast to the stark image of those who ventured to write down their intimate histories, lives, loves, hates, needs, tolerances, even futures. They mean more than just what is said in them.

Kim Rushing’s Parchman offers readers and viewers a heart-achingly frank look into life at Parchman farm. Rushing’s humanist photographs offer us a glimpse into the stark ordinariness of prison life, and the letters and notes from the prisoners give readers an inkling of the inmates’ interior lives. Parchman shows us that incarceration does not end life, but rather shifts it to a place of monotony, worry, and anxiety. This book does not ask for sympathy for its subjects, it simply demonstrates that the world within the prison’s walls and fences is as complex and frustrating as the world beyond its walls.

R. Kim Rushing has taught photography at Delta State University for twenty-three years. His photographs have appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers, including the New York Times and Garden and Gun.