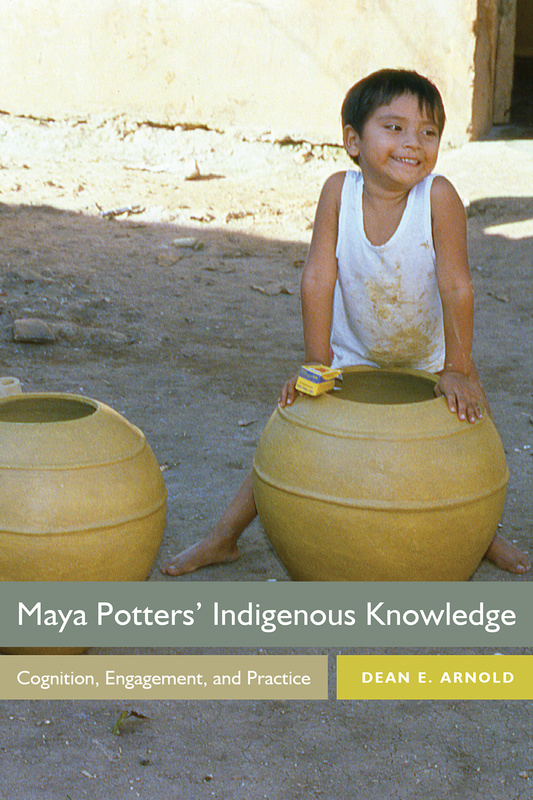

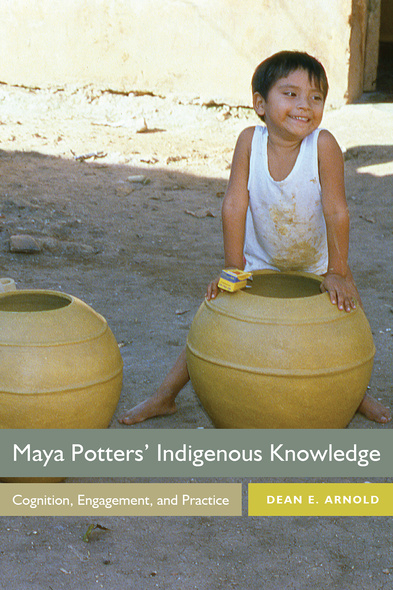

Maya Potters' Indigenous Knowledge

Cognition, Engagement, and Practice

Based on fieldwork and reflection over a period of almost fifty years, Maya Potters’ Indigenous Knowledge utilizes engagement theory to describe the indigenous knowledge of traditional Maya potters in Ticul, Yucatán, Mexico. In this heavily illustrated narrative account, Dean E. Arnold examines craftspeople’s knowledge and skills, their engagement with their natural and social environments, the raw materials they use for their craft, and their process for making pottery.

Following Lambros Malafouris, Tim Ingold, and Colin Renfrew, Arnold argues that potters’ indigenous knowledge is not just in their minds but extends to their engagement with the environment, raw materials, and the pottery-making process itself and is recursively affected by visual and tactile feedback. Pottery is not just an expression of a mental template but also involves the interaction of cognitive categories, embodied muscular patterns, and the engagement of those categories and skills with the production process. Indigenous knowledge is thus a product of the interaction of mind and material, of mental categories and action, and of cognition and sensory engagement—the interaction of both human and material agency.

Engagement theory has become an important theoretical approach and “indigenous knowledge” (as cultural heritage) is the focus of much current research in anthropology, archaeology, and cultural resource management. While Dean Arnold’s previous work has been significant in ceramic ethnoarchaeology, Maya Potters' Indigenous Knowledge goes further, providing new evidence and opening up different concepts and approaches to understanding practical processes. It will be of interest to a wide variety of researchers in Maya studies, material culture, material sciences, ceramic ecology, and ethnoarchaeology.

‘A very refreshing look at the nature of Maya pottery production. . . . it will open the eyes of many researchers to the depth of indigenous knowledge on pottery production and to a new way of thinking about the relationship between the potter and his/her raw materials.’

—Michael Deal, Memorial University

‘Studies like this are very important indeed. Arnold’s research is aimed at bridging the gap between static archaeological phenomena and the dynamic social, cultural, and cognitive aspects of behavior. The end result is a bridging argument or middle-range research that sometimes is the only way to understand the complex relationship between the fragments of matter that make up the archaeological record and the human behavior behind this material record.’

—Eduardo Williams, El Colegio de Michoacán

'Brilliant. . . . This book is for anyone who is interested in or who studies Maya ceramics, either ancient or modern. It is for anyone interested in indigenous art or in the process of artistic production, either inside or outside the academy. It is for artists, art historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, for professional scholars, or a generally interested public. Indeed, the book should be required reading for anyone focused on Maya ceramics.'

—The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology

'[Arnold] is the world's most prolific and accomplished scholar of ceramic ethnoarchaeology. . . . Most useful to those deeply involved in the ethnographic study of craft production and to archaeologists focused on ceramics.'

—CHOICE

‘There is much food for thought in this new book that archaeologists should consider in evaluating their own data. . . .The result of this volume is that Arnold has created a new way of thinking. . . .This is a cogent, thought-provoking book with compelling data and persuasive arguments, and belongs on any anthropologist's bookshelf. ’

—SAS Bulletin

‘Zack’s book should be evaluated as the third and greatest contribution in publicizing the Lisu in the wider world. . . .It’s not just a page turner—it is a valuable record of her association with the Lisu people over thirty years.’

—Anthropos‘Once again, Arnold has produced a volume that is both data-rich and theoretically challenging.'

—Journal of Anthropological Research