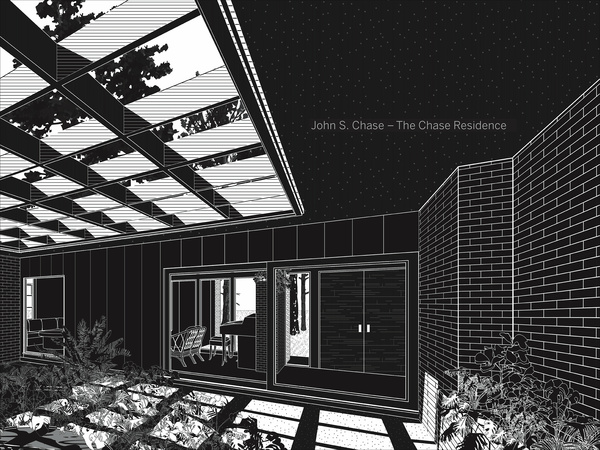

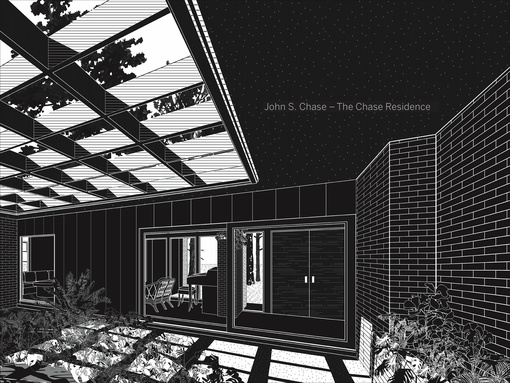

The low-slung brick home that architect John Saunders Chase completed for his own family in 1959 was Houston’s first modernist house with a true interior courtyard, a form with which other progressive architects were only starting to experiment. It was equally radical that he built it at all. When Chase graduated from The University of Texas School of Architecture in 1952—the first African American to do so—no Houston architecture firm would hire him. Chase petitioned the state for special permission to take the licensing exam, becoming the first African American registered as an architect in Texas. By 1959, he ran his own thriving firm and had established a position of remarkable influence in Houston’s social, political, and economic life. The Chase Residence, in both its original version and after a fundamental alteration undertaken in 1968, is a testament to Chase’s accomplishments.

Beautifully illustrated, John S. Chase—The Chase Residence examines how the architecture of this seminal but little-known house frames the life lived within it. It places the house in the larger context of Chase’s architectural career and his times. The book is also intended for readers broadly interested in the relationship between American architecture and society.

John S. Chase—The Chase Residence takes a magnifying glass to Chase’s trailblazing career, providing context to the history of Black architecture in the American South.

What makes John S. Chase—The Chase Residence so unique is its unprecedented look beyond the checklist of firsts, as [David] Heymann and historian Stephen Fox shed much needed light on Chase’s actual work as an architect. They do this by offering a thoroughly detailed ode to Chase’s most personal project: his dream home.

With detailed new drawings, candid family photos, and personal anecdotes based on interviews with Chase’s wife, Drucie, and other relatives, Heymann traces how the iterations of the home reveal the architect’s growth as a designer and community leader, as well as his evolving aesthetic, which, earlier in Chase’s career, tended toward Mies, then later skewed Wright. Fox, an architectural historian, frames Chase’s work in the broader historic and cultural context of the time.

[John S. Chase—The Chase Residence] demystifies how Chase fashioned a space to fit his family—and simultaneously fixed his place in architectural history.

A slender, handsome book.

[John S. Chase—The Chase Residence] paints a wonderful picture of his career. The anecdotes that fill this book provide insight into the architect’s life and place him alongside his contemporaries...I appreciate the step that the authors took with this book. It is important that people use their platforms to tell as much of the truth as can be uttered. There are too few stories of the successes of people of color in white-dominated arenas. The telling of these stories can help change tokens to trailblazers. Historical truth can aid in fostering a more diverse and representative tomorrow in architecture. This book is a fine step in the right direction. It is to be hoped that, as time passes, we’ll see more and more of these accounts, told by a variety of writers from different backgrounds.

[John S. Chase—The Chase Residence] has reignited an interest in the architect’s legacy and in how he embraced Modernism, a movement that rejected ostentatious flourishes in favor of function and utility. It makes the case that the home Chase designed for his family on Oakdale Street, a quiet cul-de-sac in Houston’s Riverside Terrace, embodied those ideals and significantly affected the city’s political and architectural history.

John S. Chase: The Chase Residence is a welcome testament to [Chase's] importance. This slim but beautifully produced book is the first dedicated to Chase and his architecture, and it provides a valuable place holder for a longer biography to follow...Understanding the experience of lesser-known public figures like Chase creates a fuller history of modern Texas that accounts for the experience of Black professionals during the civil rights era.

David Heymann, FAIA, is the Harwell Hamilton Harris Regents Professor at The University of Texas at Austin. His work examines the complex relationships of constructions and landscapes. Heymann is a contributing writer for Places Journal and author of My Beautiful City Austin. Design honors for his architectural work include selection for Emerging Voices by the Architecture League of New York.

Stephen Fox is an architectural historian, lecturer at the Rice University School of Architecture and the University of Houston’s Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture, and Fellow of the Anchorage Foundation of Texas. His work focuses on architecture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in Houston and Texas. Fox examines the ways that architecture engages such social constructs as class identity, cultural distinction, and regional differentiation. He is the author of the AIA Houston Architectural Guide and The Country Houses of John F. Staub.