Along with the Harley-Davidson motorcycle, hot rods and custom cars are powerful symbols of resistance, rebellion, and the high-octane lifestyle. Since the 1950s, these flashy restyled automobiles have occupied a unique place in American popular mythology.

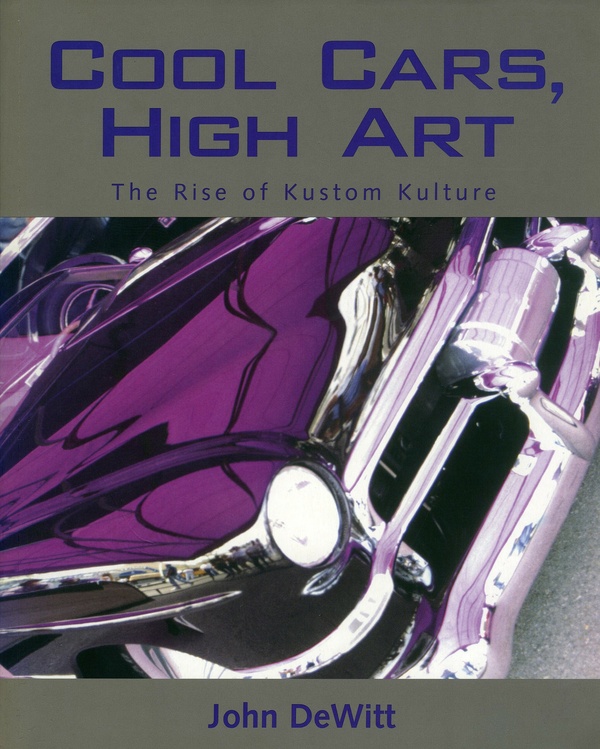

Cool Cars, High Art: The Rise of Kustom Kulture checks out this particularly male subculture with an up-close look at customized car art and the artists who create it. Through amazing technical mastery, coupled with a uniquely American imagination, these motorheads transform mass-produced products of industry into unique hand-crafted pieces of art called “rods” and “customs.”

This first full-length study to focus on the practice of hot rodding and car customizing argues not only that this “kustom culture” deserves consideration as a source of legitimate art forms but also that the rise of American car customizing reflects the attitudes and ideas of the teen culture that emerged in the 1950s. While tracing the evolution of styles, this book examines specific cars and the progression of car culture through the 1990s.

Cool Cars, High Art: The Rise of Kustom Kulture argues moreover that in this car art the theories of modernism meld with popular culture. In their beauty, in the sophistication of their designs, and in their formal play, these transformed, reimagined cars parallel the ideas, techniques, and achievement of high-art modernists. And as high art progresses into postmodernism, so too does customized car culture.

Despite the longevity and the magnitude of Kustom Kulture, this far-reaching contribution to American art has largely been ignored by mainstream critics. While postulating the cause of this anomaly, this book questions what is meant by art and how preconceived notions of gender, race, and class often prevent the recognition of creativity in places where imagination is not anticipated.

One consequence of the twentieth-century project to break down the barriers between popular and fine arts is the aesthetic discussion of objects and media not previously considered artistic, such as comic strips, photographs, quilts, and customized cars, the objects of DeWitt’s incisive appreciation in this lavish book. Right off the bat, DeWitt discloses his investment in the subject with an account of his ‘50s Friday nights, which began by ‘attend[ing] to the hygiene’ of his ‘metallic blue, nosed and decked, lowered 1953 Chevy.’ He belongs to the largest cohort of custom-car aficionados, former post-World War II teenagers who injected the new ‘50s youth culture into the small, mostly West Coast, working-class men’s avocation of modifying stock cars into hot rods, capable of much greater speeds, and custom cars, intended to look much better than what rolled off the assembly lines. The marriage of custom cars and ‘50s youth fashions stuck, but before he ponders the implications of that, DeWitt backtracks. He explains why customizing is an art medium, demonstrating that customizers approach their work the same way fine artists do, and likening the ground rules of customizing to those of cubism and surrealism. He analyzes the various styles of customizing and distinguishes periods in the now 60-plus-year history of the practice. Finally, he weighs the symbiosis of the ‘50s and customizing and its implications for the future of customizing. Throughout, he refers with pinpoint pertinence to the fifty-six figures and sixty-five color plates that make the book itself quite a dream machine.

John DeWitt is associate professor of English and acting director of the liberal arts program at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. He is also author of several books of poetry and has been published in the New American Review and New Geography of American Poets.