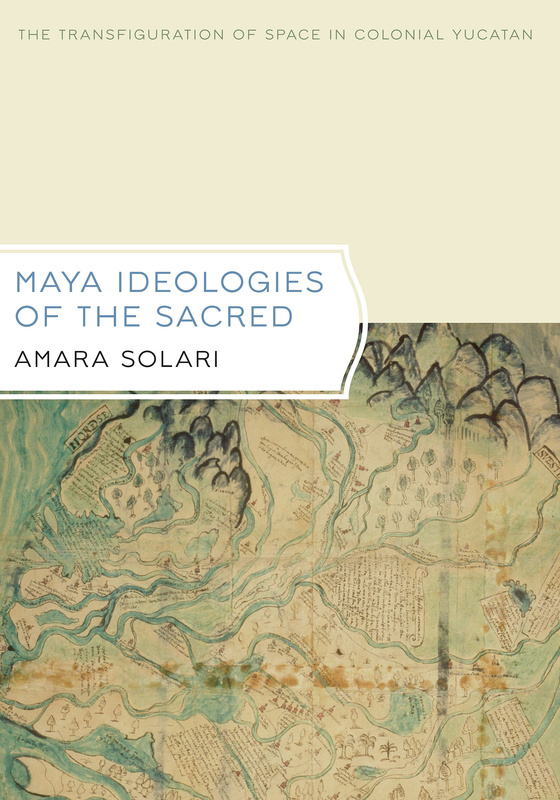

Maya Ideologies of the Sacred

The Transfiguration of Space in Colonial Yucatan

As Spaniards built colonies in the New World, men of the cloth saw within ancient ruins and inhabited native towns great potential for easing the colonization effort. In the Yucatan, which is the locus of this study, Franciscan friars seized upon the opportunity to “conquer” Maya places for Christianity. Their practice of remaking a Maya town into a Christian town—often building their church on the very foundations of an ancient sacred site—represented the absolute triumph of their religion, the ultimate defeat of the pagan demonic forces by the true faith.

This book addresses the Franciscan evangelical campaign of sixteenth-century Yucatan and investigates how Maya conceptions of space, landscape, and history influenced the conversion strategies adopted by the friars. Amara Solari analyzes colonial manuscripts written in Yucatec Mayan to discern how Maya communities conceived of land (and more abstractly, space) and how they encoded space with cultural significance. She demonstrates how these indigenous understandings of space and its history, a locale’s “spatial biography,” made the transference of sacrality possible. Using the Maya city of Itzmal as a case study, Solari examines the process of transferring sacrality and healing abilities from the Maya deity Itzamnaaj to a numinous statue of the Virgin Mary. She also reveals how the hybrid religious ideology that evolved allowed the native Maya population to subvert colonial political and religious programs and maintain community identity in the early years of the colonial period.

Solari’s skillful use of diverse sources—visual, textual, and architectural—in Spanish and Yucatec Maya makes Maya Ideologies of the Sacred a compelling interdisciplinary study that contributes to the fields of art history, colonial Latin American history, Maya studies, anthropology, architecture, and spatial theory.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book, and I can strongly and enthusiastically recommend it. . . . To my knowledge, no scholar of Maya art history has undertaken such a monumental study of the meaning of space in colonial Maya art and architecture using the framework of spatial theories . . . . The analysis here is fruitful and very illustrative of local indigenous responses to the imposition of Catholicism and the colonial Maya agency involved in refashioning, or restructuring, of sacred spaces in the colonial context. . . . Solari has successfully challenged some of the field’s most basic concepts concerning the nature of Catholic conversion and the Maya reception/rejection/adaptation of Catholicism and its understanding of all things sacred. . . . This book has the possibility . . . of becoming one of the standard works on the study of colonial Maya art history.

These are the recollections of Alexandre—of his life, his death-in-life, and his ultimate death, as they are played out against the mobile tapestry of the valley where he was born. The valley itself, in the backlands of the state of Bahia, Brazil, alternates at different stages in Alexandre’s consciousness between reality and symbol. It swings from a harsh regional specificity to become the panorama of all human life, its endless, eroding wind the devouring hostility of all environments and its pain the pain of every human being in the face of his own brutality and that of others.

Throughout the novel Alexandre’s mind ranges from sharp awareness, through hallucination, to oblivion (“a man dies while alive,” says Jeronimo, his mentor), and back again as he experiences the violent, obtuse phenomena of life in the valley—his universe and ours. This latter-day Lazarus leaves the resisting hills and black sky once only, hounded by the valley dwellers who believe he has murdered his wife, her father, and her brother. Yet despite his awareness of the horror of the valley and his intuition of something beyond it, it is precisely his contact with the gentler existence to which he escapes that forces Alexandre to recognize his nature for what it is. Turning his back on a greater and more varied range of feeling and experience, he chooses the narrow ferocity of the valley, to which he returns to die the final death for which the earlier deaths have prepared him.

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Orthography

- Chapter 1: Spatial Conquests of the Yucatan Peninsula

- Chapter 2: The Ritualized Landscape of Pre-Columbian Itzmal

- Chapter 3: Animated Landscapes in Text and Image

- Chapter 4: Cartographic Narrative and Maya Spatial Ideologies in Literature

- Chapter 5: Circular Cosmologies and Colonial Maya Cartographic Practice

- Chapter 6: The Transfiguration of Colonial Itzmal

- Conclusion: The Seventeenth-Century Transference of Locative Power

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index