216 pages, 6 1/8 x 9 1/4

4 b-w images, 22 color images

Paperback

Release Date:15 Jan 2021

ISBN:9781978806030

Hardcover

Release Date:15 Jan 2021

ISBN:9781978806047

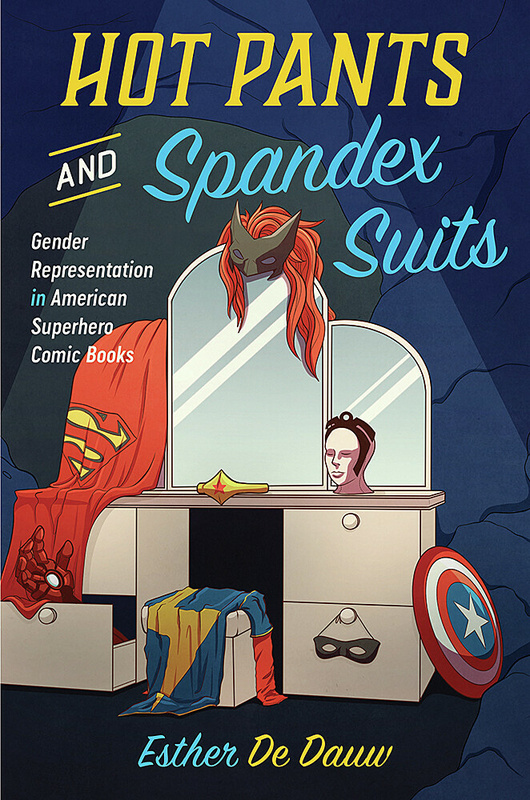

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits

Gender Representation in American Superhero Comic Books

Rutgers University Press

The superheroes from DC and Marvel comics are some of the most iconic characters in popular culture today. But how do these figures idealize certain gender roles, body types, sexualities, and racial identities at the expense of others?

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits offers a far-reaching look at how masculinity and femininity have been represented in American superhero comics, from the Golden and Silver Ages to the Modern Age. Scholar Esther De Dauw contrasts the bulletproof and musclebound phallic bodies of classic male heroes like Superman, Captain America, and Iron Man with the figures of female counterparts like Wonder Woman and Supergirl, who are drawn as superhumanly flexible and plastic. It also examines the genre’s ambivalent treatment of LGBTQ representation, from the presentation of gay male heroes Wiccan and Hulkling as a model minority couple to the troubling association of Batwoman’s lesbianism with monstrosity. Finally, it explores the intersection between gender and race through case studies of heroes like Luke Cage, Storm, and Ms. Marvel.

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits is a fascinating and thought-provoking consideration of what superhero comics teach us about identity, embodiment, and sexuality.

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits offers a far-reaching look at how masculinity and femininity have been represented in American superhero comics, from the Golden and Silver Ages to the Modern Age. Scholar Esther De Dauw contrasts the bulletproof and musclebound phallic bodies of classic male heroes like Superman, Captain America, and Iron Man with the figures of female counterparts like Wonder Woman and Supergirl, who are drawn as superhumanly flexible and plastic. It also examines the genre’s ambivalent treatment of LGBTQ representation, from the presentation of gay male heroes Wiccan and Hulkling as a model minority couple to the troubling association of Batwoman’s lesbianism with monstrosity. Finally, it explores the intersection between gender and race through case studies of heroes like Luke Cage, Storm, and Ms. Marvel.

Hot Pants and Spandex Suits is a fascinating and thought-provoking consideration of what superhero comics teach us about identity, embodiment, and sexuality.

In Hot Pants and Spandex Suits: Gender and Race in American Superhero Comics, Esther De Dauw has addressed the complexities of identity politics reflected in superhero comics from their earliest appearance eighty years ago. The superhero, a metaphor for the concerns of our culture, presents an apt topic for our understanding of the intersections of gender, race and national identity. The eighty-year span of the book offers us a mirror to our changing perceptions of identity politics and it is of interest to anyone interested in cultural, historical and media studies.

Dr. Esther De Dauw asks us to reconsider the generic construct of the superhero and to ask not only who they serve, but how. More importantly, she shows how their high-minded words often obscure less lofty silences and thus also asks us who they be might harming.

Esther De Dauw’s book Hot Pants and Spandex Suits is well versed in gender and sexuality studies.

ESTHER DE DAUW is a Leicester, UK based comics scholar, who works on superheroes, gender and race. She has published in The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, contributed a chapter to the edited volume Unstable Masks: Whiteness and American Superhero Comics, and was the primary editor for the collection Toxic Masculinity: Mapping the Monstrous in our Heroes.

Introduction

For almost eighty years, superheroes have been a part of American mass media, and, through the increased presence and popularity of superhero films and TV-shows, are now considered a staple of American culture, exported to international audiences in several different mass media formats. Originally appearing in comic books, superheroes have also appeared in syndicated newspaper strips and radio serials, animated cartoons, TV series, films and original web content. Most mainstream audiences are accessing the superhero outside of comic book content, through the Marvel Cinematic Universe (2008-ongoing), hereafter referred to as the MCU, Netflix' series and the CW Network's TV series.[1] With wide ranges of products serving as superhero merchandise (literally anything you can slap a hero's chevron or face on), superheroes being adopted for various political and social movements, and Avengers: Endgame (2019) bringing in a world-wide $2.796 billion at the box-office, labelling it the highest grossing film of all time, it is safe to say that the superhero is at least as culturally present now as when they first took the world by storm.[2] Arguably, with everyday life increasingly saturated with mass media and advertising, the superhero is more present than ever and, like many other comic scholars, I want to dig into what it is they say about and to us. Situated at the intersection of comic studies, cultural studies and theories of structural power-relations, this book discusses superheroes in their socio-historical context and determines how they are informed by dominant gender ideology in the American cultural landscape.

A History of the Industry

In this book, I mostly focus on the comics instead of the films or TV-shows that superheroes appear in, which warrants a brief history of the medium. Despite film and TV's ability to reach a wider audience, the sheer amount of comic titles produced, with roughly 75 monthly comic book titles published by Marvel and 73 by DC at the time of writing, points to comics as being the superhero's dominant media format. Additionally, TV shows and Hollywood movies are considered adaptations of the comics and thus, comics remain the primary medium dictating the shape and form of superhero content, even as other media content also influences comics.[3] As the original progenitor of the superhero, the comic book medium and its industry has significantly defined the concept of the superhero.[4] The industry's history was initially documented by fans and expert-practitioners, who used labels that Marvel and DC adopted to categorise the different ages of comic book development: Golden Age (1930s-1950s), Silver Age (1950s-1970s), Bronze Age (1970s-1980s), Dark Age (1980s-1990s) and Modern Age (1990s - Ongoing) Age. Each Age is supposedly defined by dominating narrative, formal or economic trends. While the exact dates of the ages (and the use of this classification) are regularly debated both in fan communities and academia, the industry generally accepts them. Discussing the "extremely articulate critique of that model" by Benjamin Woo, Orion Ussner Kidder writes that Woo "contends that the terms are inherently antithetical to academic rigor."[5] As Kidder states, agreement with this analysis does not preclude the usefulness of these terms, considering its use by the industry, professionals, fans, creators, experts and the academic field. Recently, American Studies scholar, Adrienne Resha, provided a compelling argument that we have entered a new stage: the Blue Age of Comic Books (2000s-ongoing), which is defined by the digitization of comic books and comic book culture's increasingly online presence.[6] When discussing history and comics, these terms are inescapable and will be used in this book when appropriate.

In June 1938, DC published Action Comics #1 with Superman on the cover for the first time. Comics were a fairly new medium and mostly consisted of collections of reprinted syndicated newspaper strips with few original storylines. Due to the popularity of these collections, publishers began to pay artists and writers for new comic book content, which led to creation of short comics and, eventually, to the publication of Superman. The immense success of this character launched the superhero genre, which dominated the comic book industry for nearly fifteen years. As Bradford W. Wright explains, "most comic books titles sold between 200,000 and 400,000 copies per issues" and "each issue of Action Comics (featuring one Superman story each) regularly sold about 900,000 copies per months."[7] Following Superman's lead, other publishers jumped on the superhero bandwagon and the market became saturated with other superheroes and imitations, which heralded the Golden Age of Comics. Historically, the Golden Age is defined by the industry's extraordinary output as well as Superman's omnipresence. While there exists, in online boards and fan communities, a nostalgic reverence for Golden Age stories, the quality of the material is often questionable. In Golden Age illustrations, the background is often blank and there is a lack of detail in objects in the foreground. There is a wooden quality to the character's bodies, most visible in stoic facial expressions, which can be partly attributed to the low quality of the paper and the cheap printing process that would have blurred any detail in the artist's original composition. Comics were popular with publishers because they were cheap to produce and finished products could be bought cheaply from artist studios or shops. Artists and writers often worked as freelancers and worked together as a studio/shop, which functioned as an assembly line with the writing, drawing, colouring, lettering and inking of the work divided among contributors. This allowed for the fast production of a fully finished product. The copyright was often transferred to the publisher as part of the sale, with the understanding that the publisher would continue to pay the shop for new issues. Many artists considered this kind of comic book work as a way to make money while they worked on their 'real art' or until they were contracted to illustrate syndicated newspaper strips, which were more respectable. Both inside and outside the industry, comic books were condemned as low brow mass entertainment. Sold cheaply, they were affordable to the largest demographic in the 1930s: the working poor.

Following the depression and unprecedented levels of unemployment across the United States, a large part of the population became subject to extreme poverty. The cultural landscape shifted in response, abandoning the "Victorian middle-class axiom" and turning to blue-collar sentiments instead.[8] The middle class shrank while the working class expanded and the working poor and unemployed reached record numbers. Superman was born in this context, with mass media focusing on the common man, who was working-class and beaten down, desperately struggling against the forces of industry and modernization.[9] As Wright writes, "[from] Depression-era popular culture, there came a passionate celebration of the common man" and his victory over the social forces set against him.[10] Especially science-fiction and fantasy offered up avenues of escape by removing the hero from the contemporary modern world, which allowed his masculine abilities to thrive, or by imbuing the hero with abilities that allowed him to conquer the modern world itself. Superman, brought into the world by avid readers of science-fiction and fantasy, could bend the world around him for the sake of the disenfranchised and the poor. His creators were also young members of the Jewish community, which increasingly rejected the tenets of laissez-faire capitalism in favour of a more social model as their community was disproportionally impacted by the Great Depression and its governmental and municipal budget cuts, as well as segregation and anti-Semitism.[11] As Aldo J. Regalado writes, Superman and the heroes that followed him are rooted in traditional American heroic discourse that sets Anglo-Saxon masculinity within the American context at the top of the racial hierarchy. While Superman set new standards for heroism and created a new image of masculinity, he did so by "redefining the ethnic and class requirements of masculinity in America."[12] Superman created a heroic category that incorporated the working-class man and expanded the concept of whiteness to include non-Anglo-Saxon European. This allowed non-Anglo-Saxon communities to buy into enfranchisement at the cost of punching down, separating themselves from a more easily 'recognizable' and identifiable Other, to conform to the dominant order. This "involved masking or de-emphasizing ethnic identity" in favour of an American national identity for white-skinned characters, "embracing models of white masculinity and, to some degree, optimistically championing the social institution of the society they hoped to be a part of."[13] Superman and superheroes like him were often vocal defenders of social justice and the (white) working class, combatting the social evils that created poverty and crime. They functioned as a power fantasy for the economically disenfranchised and the phenotypically white immigrants who found themselves excluded from mainstream society.

This process of breaking open the category of whiteness was accelerated through World War II, as superheroes increasingly fought Nazis who were portrayed as a European Other. This placed Nazi racism in contrast to American values, such as democracy and freedom, further framing white American identity as a noble and powerful force for good. In this way, American superheroes demonstrated that a (phenotypically) white American identity was the central requirement for powerful masculinity, displacing Anglo-Saxon or Germanic ancestry as a prerequisite for whiteness. As Regalado writes:

Having redefined whiteness in more inclusive terms, American superheroes consolidated these gains for their creators by increasingly resorting to traditional strategies of pitting white masculine heroes against racially defined "others." This trend became even more pronounced as the Second World War created opportunities for marrying more inclusive notions of whiteness to a national cause.[14]

Essentially, the war provided Superhero comics with the opportunity to define white masculinity, elevating the white American above other whites and the Racial Other. While this initially sustained a superhero boom, the focus on white men to the exclusion of white women also contributed to the initial, gentle decline in sales in the late 1940s, foreshadowing the 1950s collapse of the superhero genre.[15] As men joined the war, women joined the workforce and increased their independent spending power. Comic books attempted to capitalize on this potential new customer base after the success of Miss Fury and Wonder Woman in 1941 by churning out female copies.[16] However, superhero comics never really recovered. At the end of the war, superhero comic books continued to lose sales while jungle, Western and crime comics began to flourish. Post-war prosperity ensured that working-class values lost their appeal and with the rise of capitalist consumer culture, the more 'social justice' orientated superhero genre could not keep up. Robert Genter writes that "the country transformed from a goods-producing society to a service-centred one and the American worker transformed from the brawny, industrial labourer from the turn-of-the-century into the conformist white-collar worker of the 1950s."[17] In the 1950s, America became increasingly middle-class and without a public eager for a working-class hero, mass media increasingly catered to the middle class and there was no need for a working class hero. Many superhero titles were cancelled.[18]

Not only did comics become less popular due to a changed demographic and competing mass media formats, such as television, the growing controversy around comic books and their possible link to juvenile crime contributed to declining sales throughout the 1950s. The backlash against comic books heavily rested on the higher and middle class understanding of intelligence as the "refinement of aesthetic taste" and fears over the subversive nature of print culture dating back to the 19th century.[19] Essentially, high-brow and low-brow culture is an artificial divide that defines the popular culture of the masses as vulgar and unrefined because of its widespread appeal while high-brow culture is morally superior based on its exclusive availability to the middle or upper class. Intelligence was understood as the ability to identify high-brow aesthetic and entertainment. Comic books embodied low-brow culture and were increasingly suspect as it "challenged the notions of order, respectability, sobriety, self-control, productivity, and character championed by adherents to the nation's capitalist mainstream."[20] Comics' status as mass media objects also drew criticism from those who feared that consumerism and luxury were corrupting influences that undermined (masculine) virtues at a time when the Cold War required American citizens to remain hardy and vigilant against communist forces. Furthermore, according to Thomas Hine, comic books were extremely popular amongst young teenagers and children, but contained increasingly violent and disturbing content. Because they were so cheap, they were often purchased by children with their own pocket money, without parental oversight, and children often brought comics to school and swapped them.[21] This decreased parental control over the comic book content that children consumed at a time when parents were already wringing their hands at the level of independence that children and teenagers increasingly displayed.[22] Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, the comic industry came under fire for corrupting the nation's youth and something had to be done.

As early as 1948, the industry devised self-regulating measures, such as a Comics Code, to deflect criticism. However, this code was ineffectual at curtailing extreme violence through a lack of any consequences for code violations. It did very little to change the industry's output and halt the growing backlash. In 1953, the United States Senate created the Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency to examine the extent of juvenile crime and its causes. Many comic book publishers were called on to testify as well as educators and child professionals, including child psychologist, Dr Frederick Wertham. While the committee concluded that there was not enough evidence to suggest that comic books directly caused juvenile delinquency, the report heavily implies that they were a contributing factor. Several states attempted to ban comic books, but bans were defeated in court through constitutional concerns regarding censorship.[23]The situation escalated when Wertham published his book, Seduction of the Innocent (1954), based on his experiences working with criminally convicted children and young people. While his book did not use a scientific method and often misrepresented evidence without referencing his sources, it was very popular. Seduction of the Innocent presented compelling anecdotal evidence and Wertham's genuine concerns for children's development clearly shines through. He was particularly concerned with the rampant racism present in all forms of popular culture and its influence over young people's morals and values. He believed in higher regulation for all forms of cultural output instead of allowing economic concerns to dictate the shape of mass media. In other words, he believed that, just because crime sells, it does not mean that it should be sold. Comics, with their hold on the nation's youth and the growing backlash against it, were an easy target. Wertham wielded the rhetoric used by Cold War warriors who chastised the nation's lack of moral fortitude, accusing comic books of promoting the kind of depravity that would infect children's minds. While he focused on crime and horror comics as the main source for juvenile crime, he also despised superheroes. He believed they were fascist and taught children, especially young girls, unnatural gender roles.[24] Pressure on the industry increased when schools and church groups organised public comic book burnings and retailers refused to sell comic books.[25] In response, the industry founded the Comics Code Authority in 1954, hereafter referred to as the CCA, to regulate its output.

The CCA consisted of a main administrator in charge of an expansive team of child care professionals. Publishers were required to pay a membership fee as well as a submission fee for every issue. Each comic would be reviewed, sent back with a list of changes to be made and issued with the official CCA stamp on completion. Retailers refused to sell comics that did not have the CCA stamp. Some publishers were able to opt out of the CCA without having their comic books boycotted by retail outlets. For example, Dell comics maintained that its line of education comics had always been beyond reproach and refused to associate its brand with less reputable publishers via the CCA. However, most publishers did not enjoy such a positive reputation and were forced to work with the CCA to get their comic on the shelves. The CCA's approval process could be time consuming and expensive. Therefore, an extremely strict adherence to the code prevented delays and loss of revenue. Most publishers immediately cancelled their horror and crime series, removed any graphic depictions of crime from their detective comics and eliminated any hints of nudity in their jungle books.[26] The CCA "was tailored to affirm the dictates of suburban home life", middle-class respectability and the validity of Cold War America's ideological opposition to the USSR, contributing to the creation of increasingly conservative comic books. Within several years, comic books came to be seen as harmless children's entertainment and, as a medium, inherently childish. As Regalado writes, they became "the type of product that could be comfortably dismissed by mature adults with anything higher than lowbrow aesthetic tastes. As such, superhero comic books largely ceased to register as blips on the cultural radars of most social reformers and concerned citizens."[27] Several small publishers perished in this environment, while those that survived returned to the older superhero genre to boost sales.

The late 1950s saw a resurgence of the superhero genre, with a new direction consisting of whimsical "what if?" narratives, futuristic technology and a combination of science fiction and fantasy. In this sense, the Silver Age (1950s-1970s) refers to a time when the CCA was initially in control although the 1960s/1970s saw increasing challenges to its restriction. It is also defined through "its expansion into television and animation, and its expansion of the superhero genre."[28] In terms of gender, the CCA required that men and women fulfilled traditional gender roles to fit in with traditional American values. Gay characters were non-existent or extremely closeted. The code explicitly prohibited the depiction of "[illicit] sex relations" and "sexual abnormalities".[29] This referred to sexual relations outside of marriage and adultery, which were a staple of pre-code detective and crime comics, as well as homosexuality. While some superheroes have retro-actively been identified as gay, like the Rawhide Kid in Rawhide Kid (1955-1957, 1960-1979), no superheroes were openly gay during this time. The CCA also specified that "[ridicule] or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible."[30] Black characters were rare in the Golden Age and most characters of colours at that time were racist stereotypes. Particularly Japanese, Chinese and other Asian characters were presented as monstrous, an evil racial Other white America had to defend itself against, reflecting fears about race and yellow peril stereotypes during World War II. While attempting to block racism in comics was a positive step forward for a self-regulating industry, the overzealous application of the code and white fears of discussing racism resulted in non-white characters disappearing from the comic pages altogether.[31] Even narratives that directly engaged with the negative consequences of racism were banned, because they showed racism and people of colour being treated poorly by white characters. As a result, racial differences became embodied by white characters who represented a racial Other or characters who had blue, green or red skin. It was not until the code was less strictly interpreted due to the increased liberalisation of American society throughout the 1960s that Black characters reappeared in comic books.

The CCA's control of the industry could not last during the 1960s and 1970s, when changes in America's cultural landscape influenced mass media. The anti-war sentiment and disillusionment with American power and authority made the CCA's insistence on a respectful depiction of authority outdated. With the invention of the first oral contraceptive pill in the 1960s and the rise of Second Wave Feminism, which argued for greater political, financial and social freedom for women, contemporary attitudes towards sex became less conservative. Simultaneously, the Stonewall Riots in 1969 generated a radical Gay Liberation movement compared to the earlier, more sedate homophile movement. The Civil Rights movement in the 1960s campaigned to end racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans, and secure their citizenship rights through legislation and social awareness campaigns. Publishers increasingly pushed the limits of the code, submitting less and less conservative issues, while the CCA increasingly interpreted the code in less conservative ways and stamped its seal of approval on issues that would not have seen the light of day a decade earlier. This led to the creation of characters such as Spider-Man (1962), the Hulk (1962) and Black Panther (1966), who challenged American institutions and pushed back against the more conservative trends in comics.

As Wakanda's representative and king, Black Panther is meant to signify the potential of Black identity outside of white European/American control. In the 1950s, growing resistance to European colonialist expansion led many African nations to seek independence from European governance. According to Adilifu Nama, Black Panther represented "African leaders [who] embodied the hopes of their people and captured the imagination of the anticolonialist movement with their charisma and promise to free Africa from European imperialism."[32] Certainly, Black Panther's resistance to colonial forces taking over Wakanda allows him to function as such a symbol, existing as "an idealized composite of third-world Black revolutionaries and the anticolonialist movement of the 1950s that they represented."[33] However, this representation was not free from racism. As Martin Lund points out, Wakanda is steeped in white stereotypes about Africa.[34] Lund discusses how, in their initial meeting with Black Panther and their first visit to Wakanda in 1966, even the Fantastic Four realize that Wakanda seems to consist almost entirely out of colonial narratives and Hollywood imagery. Wakanda is surrounded by a 'primitive' and 'undeveloped' jungle which "recalls notions about the African continent as nature-rich but underdeveloped 'terra nullius, that is, vacant land,' ripe for white interference" (original emphasis).[35] The insistence on Wakanda's technological developments, implying a Western view of progress as automatically taking similar routes as Western nations, does not negate the representation of Wakanda as exotic, barbaric and undeveloped or culturally unsophisticated.

The 1960s also saw the rise of organised comic book fandom, when Julias Schwarz, the editor-in-chief for DC comics, added full addresses in the letter columns at the back of comic books, which allowed comic book fans to communicate with each other.[36] Once communication was established, the publication of home-made, small-scale fan magazines (fanzines) distributed through the postal system created a thriving fan culture that discussed all aspects of superhero comic book production. This included social issues and how they were handled in comics as well as the CCA and censorship. Fanzines became social spaces where the community shared their enthusiasm for the medium and for specific characters, recounting stories of visiting car boot sales to find old issues of favourite characters.[37] Fan communities, who fondly discussed old superheroes they'd read as children in the 1940s, imbued these 1940s superheroes with new meaning, which Schwarz capitalised on by reviving old superheroes that had gone out of publication. Fan activity was heavily encouraged by Marvel and DC, who used these communities as free market research and advertisement, as fanzines provided a direct pipeline to their customer base and allowed them to cultivate brand loyalty.[38] This direct interaction between fans and the industry created loyal fans, not just to companies but also to artists and writers, who were able to use their popularity as a bargaining tool to increase pay, negotiate royalty payments and maintain greater (although still limited) control over their intellectual property. However, it became increasingly clear that the stories fans wanted to read could not be published in the CCA's controlled market.

Mainstream media's lack of interest in comics, combined with the increasing push against the CCA's limits by fans, led to the code's re-write in 1970. This ushered in the Bronze Age (1970s-1980s), where female characters could wear more revealing clothing and implied sexual contact was permitted. However, it still prohibited "violations of good taste or decency," which was sufficiently vague enough to leave its application open to interpretation.[39] The 'Marriage and Sex' section stipulated that "[sex] perversions or any inference to the same," which was code for homosexuality, "was strictly forbidden."[40] The code effectively prevented comics from engaging openly with queer characters and, as a result, Marvel created a 'subtle' gay character in 1979 called Northstar, a member of Alpha Flight, the Canadian superhero team.[41] His civilian identity was Jean-Paul Beaubier, a French-Canadian Olympic skier, who was never seen dating women because he was too focused on his career to commit to a relationship. During the 1980s, Northstar contracted a mysterious illness, which resulted in a hacking cough and limited healing/recovery abilities, which was rumoured to be AIDs. However, the storyline was squashed by Marvel as AIDS was still considered to be a 'gay disease' and supposedly would have outed Northstar as gay to the general audience. Instead, his illness became the result of a cosmic disturbance interfering with his mutant powers.[42] The new code did not update its previous restrictions on religion or race, but these rules were now interpreted less conservatively, which allowed for the rise of Black superheroes. These Black superheroes, such as John Stewart as the Green Lantern (1971) and Luke Cage as Power Man (1972), were the first attempts to create Black superheroes who actually resembled real-life minorities. However, these were still mostly written by white writers, depicted by white artists and under the control of white editors. As Derek Lackaff and Michael Sales write, these characters were not as progressive as Black readers might have hoped for:

In the 1970s, these attempts to introduce Black faces left many Black comic book readers unsatisfied. Black characters were often given a heavy-handed stigma that immediately marked them as the 'racial' character, especially with their names, Black Panther, Black Lightening, The Black Racer, Brother Voodoo, Black Goliath, Black Vulcan, Black Spider.[43] Black superheroes suffered from tokenism and being 'marked' as the single Black superhero. These stereotypes persisted through the 1980s and 1990s, although they became increasingly diluted because of growing social awareness.

Throughout the Bronze Age, comics also became more violent, especially towards female characters. While the CCA did state that rape or sexual assault "shall never be shown or suggested," physical violence against female characters continued to rise.[44] Often contributed to the backlash against feminist gains, mass media in the 1980s American landscape increasingly depicted violence against women.[45] On the one hand, it did this by creating 'strong' female action heroes who could physically enter combat and go toe-to-toe with any male character as a move towards feminism. On the other hand, it also increasingly killed and mutilated women in action and horror films. In comics, the 1980s saw the publication of comics such as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986) by Frank Miller, Watchmen (1986-1987) by Alan Moore and David Gibbons as well as Batman: The Killing Joke (1988) by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland. These works contained high levels of violence against women, as well as anti-establishment sentiments, which would have made them unpublishable only twenty years earlier, but which the increased normalization of violence and sexual imagery in the American mass media of the 1970s and 1980s allowed. These publications are often considered the first products of the Dark Age of Comics (1980s-1990s) and the impact they had on the industry is substantial. They contributed to the growing cultural notion that comics had to be more realistic, which meant 'gritty' and dark compared to the more camp, fantastical variety of the Silver and Bronze Age, and should be marketed to adults to elevate the medium.[46] This contributed to the still-popular notion that books involving violence and sexual trauma are inherently more artistic, speak to the human experience in a way that happier or less traumatic books cannot, and that these texts are more worthy of study than camp or 'silly' narratives. While, increasingly, new comic scholars are strongly criticizing this understanding of 'dark comics', it is an attitude that disappointingly continues to exist both in the industry, among fans and comic scholarship.

Throughout the Dark Age, the relationship between fans and creators shifted again as older fans entered the industry as creators and professionals. This hastened the demise of the CCA as fans-turned-creators made the more radical comics they had wanted to read as teenagers in the 1960s and 1970s. Furthermore, the fan culture's investment in documenting comic history and tracking continuity seeped into the industry, who began to streamline continuity and published books and guides on comic book ages. The sale of these was facilitated through the emergence of the direct market: small, independent comic book shops run by fans who sold not only comics but also all comic-related paraphernalia.[47] This weakened the CCA's power, as a main incentive for companies such as Marvel and DC to adhere to it lied in retailers' refusal to sell comics lacking the CCA seal of approval. Specialty shops, however, did not ban non-CCA comic books. These shops also narrowed the demographic of comic book fans. As Carolyn Cocca writes, the "increasing number of specialized comic shops, higher sticker prices due to higher paper costs, suburbanization, a royalty system and a focus on high sales of superhero comics and merchandise tended to concentrate the comic fan base - it seemed to be mostly male, white and older" and as these shops were run by this fanbase, "many also fostered exclusionary cultures that deterred new and/or demographically different readers."[48] Essentially, comic book shops allowed comic book creators to cater to their fans' wishes more directly, and with the shop functioning as a gate keeping mechanism, these wishes resulted in 'sexier' and more violent comics catering to straight, white men.

In 1989, the CCA updated the code to reflect the increased acceptability of adult themes in comics and had less restrictions on homosexuality, sex and race. The 'Characterizations' section stated that:

Character portrayals will be carefully crafted and show sensitivity to national, ethnic, religious, sexual and socioeconomic orientations. If it is dramatically appropriate for one character to demean another because of his or her sex, ethnicity, religion, sexual preference, political orientation, socioeconomic status or disabilities, the demeaning words or actions will be clearly shown to be wrong or ignorant in the course of the story. Stories depicting characters subject to physical, mental, or emotional problems or with economic disadvantages should never assign ultimate responsibility for these conditions to the character themselves. Heroes should be role models and should reflect the prevailing social attitudes.[49]

While this version of the code seems to clearly promote equality and positive representation of minorities, its reference to "prevailing social attitudes" still leaves a loophole subject to personal and subjective interpretation.[50] Certainly, the characters produced during this time fell into what was then considered positive representation, with non-white, non-straight, non-male characters acting 'normal', which is a concept rife with preconceived notions about what people should be and maintains the status quo through the perpetuation and exaltation of normative behaviours. The 'Attire and Sexuality' section quoted "decency" and "good taste" when referencing adult sexual relationships, and made no specific mention concerning the depiction of homosexuality.[51] As a result, in 1992, Northstar finally came out of the closet, although his sexuality was barely ever mentioned again or alluded to in subsequent publications. Gareth Schott, in his excellent analysis of the character, writes that "[while] Northstar was initially held up as a gay icon, his impact quickly faded with fewer appearances, some as only a secondary character. Northstar did resurface, only to be killed, resurrected, brainwashed, saved and then cured."[52] Northstar's progressive potential was lost as he never seemed to rise above tokenism. Instead, his 'subtle' sexuality is exemplary of how, for most of comic book history, gay superheroes were invisible (to a straight audience). The 1989 code makes no separate mention for race or racism. Most Black characters introduced in the 1970s disappeared again by the late 1980s as blaxploitation's popularity plummeted. Other ethnic minority superheroes were even slower to appear and again, comics interacted with their heritage in a way that was either a) rife with socially acceptable stereotypes, b) lumping individual cultures together in a racist potluck of 'it's all the same' or c) whitewashing of ethnic minority cultures.

At the beginning of the Modern Age (1990s-now), DC and Marvel increasingly began to publish issues or titles without the CCA seal of approval.[53] With the rise of the direct market, comics were increasingly seen as a popular medium with a large customer base and Marvel and DC attempted to capitalise on the collector mind-set through the production of variant covers, special editions and shocking storylines that generated attention even in the mainstream media, such as the death of Superman (1992). Outraged by the commercialisation of the comic medium, many fans left the community and the backlash caused a massive drop in sales. The inflation of limited edition and special issues, which attracted collectors, also attracted buyers with an eye to save and re-sell the issue when they became more valuable. This contributed to the dismantling of comic shop communities. The direct market collapsed, with many small and local comic book shops closing and Marvel even declaring bankruptcy in 1996.[54] By the early 2000s, DC and Marvel were desperate to regain a customer base and were willing to take risks to do so: the CCA was disregarded entirely. In theory, comics were now allowed to include any kind of material they wanted. However, it was not through comics that superheroes became relevant again. Instead, superheroes became culturally relevant for children through cartoons, such as the DC Animated Universe (1992 - 2006), and through films for adults, such as Blade (1998), Hulk (2003), Daredevil (2003) and Elektra (2003). While these films are now often lambasted by fans as poorly written and acted, they were moderate commercial successes at the time. Comic book sales slowly started to rise again, but even without the CCA, most superheroes were still straight, white and male.

While female characters had seen some increase in numbers in previous ages, only a few superheroes came out as gay and, at the time of writing, gay superheroes remain low in number. Some gay superheroes have had their sexuality confirmed by editors or authors, but have not openly stated or acted on their sexuality in any publication, such as Catman from Gail Simone's Secret Six (2005-2006, 2008-2011).[55] Those who are openly gay are either in a relationship, or are perpetually single. In 2006, Batwoman was marketed as DC's first openly lesbian superhero to hold her own titular comic and was explicitly framed as DC's high-profile lesbian character, intended to be part of DC's regular line-up and slotted to join the planned Justice League comic before it was turned into a miniseries. In 2007, Renee Montaya, an established lesbian character in the DC universe, resigned from the Gotham City Police Department (GCPD) after being outed at work and became the new Question. The New 52 reboot also introduced new gay characters, such as Bunker (team member of the Teen Titans), and Gravity Kid and Power Boy (members of the Legion Academy), but these new gay superheroes have received very little media attention, have not appeared in many publications and have no merchandise. The reboot also impacted Renee Montoya's storyline as she appeared once again as a member of the GCPD instead of a superhero in 2015.

In 2012, Northstar received considerable media attention when Marvel announced his wedding to his long-term partner, Kyle Jinadu, in order to celebrate New York's legalisation of gay marriage in 2011. The wedding received an extraordinary amount of publicity from Marvel who promoted it with the tagline "Save the Date" as the event of the year.[56] This kind of attention raised a few questions. Would a marriage between two heterosexual characters draw the same sort of attention? The wedding between Superman and Lois Lane in 1996 certainly did, but that was a relationship with sixty years of history.[57] If most heterosexual couples would not receive this kind of attention, the attention that Marvel's 'gay' wedding received can be read as a celebration of progressive values or an attempt to cash in on current events, targeting a new potential audience. Marvel was eager to present the wedding as a representation of how comics were becoming more progressive and in-tune with contemporary morals and values.[58] Another long-term romantic couple in the Marvel Universe are Wiccan and Hulkling, two members of the Young Avengers superhero team who became engaged in 2012. In 2015, in one of the more convoluted storylines detailed in All New X-Men (2012-ongoing), the original X-Men team from the 1960s travel to the future (current times) and the young, 1960s' era Jean Grey discovers that the 1960s' era Ice Man is gay by reading his mind. The team discusses how the Ice Man who lives in current times never came out or even seemed to realise that he was gay, which means that Jean's discovery has potentially altered 1960s' era Ice Man's future. However, the comic does not address Jean's violation of Ice Man's privacy and the potential dangers of outing someone without their permission or consent. It seems that in the 2010s, gay superheroes are simultaneously losing and gaining ground.

In addition to an increase in gay characters, the Modern Age also saw more Black characters join the ranks of the superhero community, such as Miles Morales as Spiderman (2011) and Batwing (2011). However, these superheroes of colour, no matter their strength or weaknesses, often take a backseat to white superheroes. As Albert S. Fu explains, "[despite] the creation of numerous heroes of colour, it is still the Caucasion-'looking' aliens (Superman), mutants (most of the X-Men) and talented humans (Batman) that are mainstream heroes."[59] Black superheroes are still less popular and well-known, often side-lined in favour of white superheroes. Often, they do not have merchandise that provides greater cultural dissemination and when they do, it is often because they are paired with a white character or have inherited a legacy name that allows their merchandise to cross race boundaries. When superheroes are lifted from the comic book pages to star in TV shows and films, non-Black characters of colour are often white-washed. For example, the white Elizabeth Olsen was cast to play the Romani Scarlet Witch in Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015) and although Dr Strange had been drawn as racially ambiguous for decades, the white Benedict Cumberbatch was cast to play him in Dr Strange (2016). While comics have a long history of rhetorically promoting acceptance and tolerance, they have failed to represent gender or racial equality through character creation and narrative drive, with recent years seeing both progress and decline, especially as superheroes re-entered the mainstream through "superhero blockbuster films, downloadable television shows, and trade paperbacks available in bookstores."[60] At the end of the Modern Age and the start of the Blue Age of Comics, superheroes were no longer contained to comics and the comic book shop.

While the emergence of the comic book shop allowed for gatekeepers to tightly control the social spaces in which comic fans gathered; the demise of small, local comic book shop and the appearance of the internet has opened up social fandom spaces. As Resha has identified in her coinage of the term the "Blue Age of Comic Books", the introduction of digitally available comic books is a considerable game-changer. She argues that the 2010s saw the start of the Blue Age of Comics, following the debut of comics retailer ComiXology in 2007, and is defined through the increased popularity of digital publication. This includes the use of "digital readers, guided reading, technology and social media."[61] Digital comics, remediated through digital readers, phone or laptop screens and diverse modes of reading, allows for further capitalizations on newer and younger audiences. Resha writes: "publishers must simultaneously appeal to an aging, homogenous group of readers and to a younger, heterogeneous group of potential readers."[62] If we consider white men to be the historical main audience of comic books, and both mainstream culture and comic book publishers indicate that they do so, potential new readers present a possibly new demographic hungry for more diverse representation who are slowly coming into their spending power. Digital comics allow for further reach and distribution, as fans do not rely on their local comic book shop to carry their preferred titles, and destabilizes the collector culture that has defined fan culture for several decades. It displaces the gatekeepers of the fan community and allows this space to be opened up to non-traditional readers. As the Silver Age saw the advent of fan communities, so does the Blue Age become defined through the vibrant online fan engagement via social media.

The increased use of online spaces has created an online culture where expressions of appreciation of any given work is primarily through the fan's interaction with the community and their engagement with the source material by transforming it instead of collecting both original source material and being able to remember every detail about it in order to provide fan-credentials to gatekeepers. While fans initially used online blogs provided by corporations, such as Livejournal or Dreamwidth, they eventually began an 'Archive of Our Own' website, often referred to as AO3, to protect fanworks from exploitation and deletion by corporations as well as possible lawsuits from the owners of the original content. Recently, in 2019, Archive of Our Own won the Hugo Award for Best Related Works, highlighting the importance of fanworks and the archive built to house it.[63] Of course, the AO3 online space is not superhero specific and caters to fans of any and all kinds of content, but it highlights how the media industries' engagement with fans is increasingly becoming more important in order to gauge "cultural capital", which is increasingly replacing ratings or sales numbers as the measure of content's success. If fan engagement is becoming the new metric, Marvel and DC's strategy of slowly catering to more diverse and younger audiences as they come into their spending power is sound. However, in the background there remains a vocal subsection of fans who protest the injection of progressive politics into comics and who 'defeminised' Avengers: Endgame (2019) by editing out all the 'feminine' and 'gay' moments.[64]

It is difficult to predict what the future of comics will look like. Certainly, at the time of writing, efforts are made to diversify comic books; include more characters of colour, characters with disabilities and characters who are part of the LGBTQIA+ spectrum. There are attempts to bring in more diverse creative teams so that authentic stories can be written for these new characters and allow them to bond with the audience. Of course, with greater visibility, with increased awareness and inclusion, comes a backlash. Some fans who want their comics to remain 'politics-free,' as in, filled with what they perceive to be non-political and 'normal' identities such as straight, white men, are increasingly resisting these attempts. It is important then to understand that there are also many comics that superficially challenge the status quo, while actively reinscribing the status quo's gender roles and associated norms and values in order to cater to both groups.

A History of Scholarship

Initially, much of comic book research was pre-occupied with justificatory strategies attempting to legitimise the medium as a source of research and with documenting comic book history. As discussed by Hannah Miodrag, this research was jumpstarted by non-academic, practitioner-theorists or experts whose work, although seminal, is increasingly scrutinized for a lack of theoretical sophistication.[65] However, much of this initial work has provided valuable insights and starting points for the incredible increase in academically rigorous and critically informed scholarship being produced in the last two decades. Furthermore, early studies provided key insights into the comic book industry, the development of comic book fan communities and the relationship between content creators, editors, the content itself and the fans, although this work was sometimes too eager to take the artists' opinion of their own work at face value. While comic scholarship has seen a rise in scholars connecting comics to socio-historical developments and academic theory, practitioner-theorists and other non-academic experts in the field are also presenting increasingly complex work. Historically, most academic writing about gender and superheroes has focused on (the lack of) female characters and their performance of gender while few male superhero characters have been subject to gender analysis. Writing on male superheroes that do include a discussion of masculinity often focus on the superhero's heroic performance in relation to their female counterparts, especially female characters' (lack of) dress, agency or unrealistic and sexualized bodily proportions. There has been a significant focus on the superhero's body as a representation of the masculine ideal. According to Aaron Taylor, the superhero body, or superbody, is of special interest as it is a "culturally produced body that could potentially defy all traditional and normalizing readings. These are bodies beyond limits - perhaps without limits."[66] Such bodies could signify and project gender in new, unique ways, potentially transcending established markers and creating new identities beyond the scope of traditional gender roles. The question is, do comics actually take this opportunity or do they remain trapped in the hegemony's consumption and restructuring or radical deviation from the norm? Comics themselves are often considered to be masculine objects: stories about men made by men for other men, containing a script of normative masculine behaviour and identity. Carol A. Stabile writes that "[the] superhero is first and foremost a man, because only men are understood to be protectors in US culture and only men have the balls to lead," which is an attitude perpetuated by comics.[67]

Regarding the superhero as a masculine concept has caused some academic research to focus on conceptualizing the female superhero as separate from the superhero. In her article, 'The Body Unbound; Empowered, Heroism and Body Image," Ruth J. Beerman draws a distinction between female superheroes and superheroines. According to Beerman, the differences exist in the way the roles themselves are gendered: "[female] superheroes are characters like a male character, but who simply happen to be women, serving more as a sidekick or supporting character to the lead, male superhero (such as Supergirl)."[68] Supergirl is classified as a female superhero because she exists as a distaff version of Superman a copy of him in girl form. Superheroines, by comparison, have their own identities, infused with femininity and womanhood, apart from a male superhero, such as Wonder Woman.[69] While such classification can be a useful tool to discuss female characters and their representations of acceptable femininity, separating sidekicks, supportive characters or (initially) distaff characters from 'real' superheroes plays into cultural notions that the 'sidekick' or 'helper roles' are more feminine, less masculine, and less worthy of recognition (or scholarship). A lack of what Beerman calls superheroines and an abundance of female sidekicks or distaff characters (compared to the non-existence of male distaff characters of female lead characters) is obviously concerning in terms of representation, but it is equally dubious to dismiss sidekicks or distaff characters because they perform superheroism in a different way from male superheroes. Furthermore, such categories make it difficult to discuss the evolution of distaff characters into legacy names, where many different characters assume a specific moniker and motif, or 'distaff' characters who go on to attain a larger cultural significance than the male character they were originally based on.

Traditionally, female superheroes have always had different kinds of power compared to male superheroes. Comics emphasise the need for physical strength and the ability to participate in physical combat, which female superheroes typically do not do, which frames their powers as weaker compared to their male counterparts. Mike Madrid writes that female superheroes "in comic books have historically been given weaker powers."[70] But how is 'weaker' defined? Assuming that 'weaker' refers to physical strength, it means that comics have fallen into the trap of valuing physical strength over other abilities, no matter their actual effectiveness in combat.[71] Most female characters do not look as physically powerful as male characters do, adding to the interpretation of female bodies as weaker and less resilient then male bodies. For instance, despite their great physical capabilities, Supergirl and Wonder Woman rarely have the sculpted musculature that male superheroes often have. It would break with the fragile feminine stereotype to see them as physically powerful and providing female characters with non-physical powers adds to the preservation of female superheroes' traditional feminine beauty. Mike Madrid writes that a female superhero "will look like a supermodel if she possesses what is known as 'strike a pose and point' powers. For as mighty as the X-Men's Storm is, she strikes a pose, extends a hand, unleashes a lightning bolt, and looks great. Just like posing for a picture in Vogue."[72] Female superheroes can be powerful as long as they are still glamorous, beautiful and sexy in the heat of combat. While comics create strong and powerful female characters, sometimes in a clear attempt to gain a larger female audience by promoting 'progressive' politics, they often fail to present female characters as active subjects by depicting them as sexual objects even while the female superhero pays lip-service to equality.

Superheroes often suffer from what is referred to in gaming culture or videogame scholarship as "ludonarrative dissonance", which is used to refer to some games' conflict between the game's narrative as told through the story and the narrative told through the gameplay.[73] Similarly, comics often create a dissonance through what the characters say vs what the character development or narrative implies. In comics, superheroes often have an explicitly articulated mission statements that advocates equality, freedom and peace. Stories focusing on superhero teams such as the X-Men are often understood as endorsing diversity and socially liberal attitudes with "the metaphor and message that drives Uncanny X-Men and its related titles [being] that of tolerance and acceptance," as Neil Shyminsky writes.[74] However, those ideals are often undermined through the genre's requirement of violence and action, character development or design and the narratives' plotlines. After all, how can a comic promote the idea of equality when their female or Black or Black female characters are sidelined, violated and killed off while the white male protagonists never die or always come back from the dead?

Simultaneously, comics have often been dismissed as being childish, or sexist and racist by mainstream popular culture, adding to comic scholarship's previous preoccupation with defending the genre as worthy of academic study. With the MCU's popularity, there is a growing backlash against Marvel and DC for racist and sexist portrayals in comics, films and TV, as evidenced by articles such as "The Superhero Diversity Problem" by Julianna Aucoin.[75] In terms of sexism, the two most common tropes associated with female characters in comics identified by fans and non-academic experts, or practitioner-theorists, are fridge-ing and the Brokeback Pose. Fridge-ing, derived from the phrase 'Women in Refrigerators', refers to the way female characters are often killed to further the main male character's plot or character development. Comic writer Gail Simone first coined the term in response to Green Lantern #54 (1994), where the main character returned from a mission and found his girlfriend's mutilated corpse stuffed in the fridge. In 1999, Gail Simone used the term as the name for her website, which listed names of 'fridged' female characters.[76] While some fans argued that violently killing women was not a sexist trend because characters who die usually come back from the dead, John Bartol, in an article posted on the original website, pointed out that characters returning from the dead are usually male and coined the term 'dead men defrosting.'[77] Fridge-in also applies to Black characters who are killed to further the white characters' plot and emotional development. For example, in 2016, the Black superhero War Machine was killed in Marvel's Civil War II and his death becomes a source of conflict between the white female Captain Marvel and the white male Iron Man. The comic consistently highlights the anguish Captain Marvel and Iron Man experience at War Machine's death, as well as their struggle to grieve and move on. This relegates War Machine's death to a plot device as the conflict between Captain Marvel and Iron Man escalates into a title-spanning, Universe-wide event.

The second trope is The Brokeback Pose, a term used to identify a common pose for female characters, which highlights both their buttocks and their breasts. Often, the only way a real person could achieve such a pose would be through a broken spine, hence the name. This trope was first identified by female fans in online communities in 2012, resulting in several articles discussing the phenomenon on websites such as ComicsBeat and TheGeekTwins, which have a significant following.[78] Although the first Brokeback Pose ever published has yet to be identified, the trend seems to occur as far back as the beginning of the Bronze Age when sexualised images of female characters became acceptable again. While not all the poses identified as Brokeback are extreme enough that the character's back would have to be broken to achieve them, all of them are clearly uncomfortable. In her analysis of "24 titles/144 issues/14,599 panels" Carolyn Cocca found that "almost every issue contains sexually objectifying portrayals of women."[79] Responses from the industry and other fans who claim that there is nothing sexist about such poses led to the creation of The Hawkeye Initiative in December 2012. The Hawkeye Initiative is a collaboration between several fan artists and artists working in the industry who re-draw Brokeback Poses with superhero Clint Barton, also known as Hawkeye. Drawn with a male character, the poses become obviously physically impossible and ridiculous, highlighting both the sexism of such poses and the way it has been normalized and made invisible when applied to female characters.[80] Female superheroes can be powerful, but only if they are sex objects and conform to other 'traditionally feminine' characteristics, preferably in service to a male characters' storyline or the male character's gaze. As Carolyn Cocca writes in her book, Superwomen: Gender, Power and Presentation:

In short, while there are a number of popular, strong, complex, female superheroes, in general what we see is underrepresentation, domestication, sexualisation, and heteronormativity. That is, there are far fewer women than men, the women are portrayed as interested in romance or as less-powerful adjuncts to male characters, the women are shown in skimpy clothing and in poses that accentuate their curves while the male characters are portrayed as athletic and action-oriented, and both women and men are almost always portrayed as very different from one another and interested only in opposite-sex romance and sex.[81]

Increasing the amount of female characters is not enough. They need to appear in narratives that support them and challenge the status quo.

Academics such as Gareth Schott, Rob Lendrum and Ramzi Fawaz have focused on the development of gay characters in comics, pointing out that gay superheroes still perpetuate stereotypes or function as token characters. Both Schott and Fawaz, as well as Kara Kvaran, discuss Northstar as the token gay man and briefly touch on the Rawhide Kid as an example of stereotypes used to imply a character is gay without openly stating so in the text. Kvaran believes that superheroes who openly state their homosexuality in the text allow for more realistic interpretation and that, despite their limitations, their inclusion is a good sign of social progress in American culture.[82] Historically, gay characters have been invisible in comics and openly gay superheroes have only been present in recent years, suggesting increased liberal attitudes to gender and sexuality in American society. However, most academic scholarship is limited to the ways in which characters are positive representation, or the ways in which these characters remain token characters who fail to challenge stereotypes. Instead, this book focuses on the representation of specific gay characters, such as Billy (Wiccan), Teddy (Hulkling) and Batwoman, and analyses how their positive representation fails to challenge stereotypes and fits into a discourse that heteronormalizes gay people, challenging how we understand 'positive' representation.

The academic research on Black superheroes has been in a similar vein to the work on gay characters, identifying positive representation vs. negative stereotyping. Other academic work has focused on excavating and identifying forgotten Black superheroes, who inspired or impacted the industry at the time of their publication, but were forgotten or buried later on. Much work has been done on identifying the cultural and historical significance of Black superheroes, artists and authors in a field that is still dominated by white men. This includes, but is not limited to, important work such as Sheena Howard and Ronald L. Jackson III's Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation, Adilifu Nama's Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes and Deborah Elizabeth Whaley's Black Women in Sequence: Re-Inking Comics, Graphic Novels and Anime. Much of this academic research agrees that the industry and superhero comics are struggling with unpacking institutionalised racism. It seems incongruent that narratives traditionally focused on fighting evil, including social evils such as racism, would struggle to represent racial equality or non-racist narratives. Discussing this discrepancy, Marc Singer analysed The Legion of Superheroes comic series (1958-1994), focusing the issues produced during the Silver Age.[83] The Legion was an intergalactic superhero team, defending the entire galaxy from evil and the team prided itself on their refusal to discriminate against any race. However, Singer notes that "the Legion's supposed racial diversity was mitigated - if not virtually negated - by the fact that, of all the races represented in the comic, only one group existed in real life: the white characters who comprised the bulk of the Legion."[84] Humans and aliens were white characters, while characters of colour were blue, green or purple and "by locating [racial diversity] in protean characters who serve as free-floating signifiers for the racial 'other' without representing any real-world race," The Legion of Superheroes never addresses the white supremacy inherent in American culture, nor does it tackle any real racial issues.[85] Instead, it "perfectly illustrates the contradictory treatment of race in many superhero comics: (…) Legion ultimately erases all racial and sexual differences with the very same characters that it claims analogize our world's diversity."[86] The comic preached diversity and acceptance of the racial Other, but never represented racial diversity in any meaningful way, supporting an ideology of equality without compromising the privilege of white hegemony. This tendency to use white characters as imaginary aliens or minorities that in no way resemble any real-world ethnicities continues to plague the comic book world.

The most well-known version of "superhero comics [representing] every fantastic race possible, as means of ignoring real ones" are the X-Men comics.[87] The first issue of the X-Men came out in September 1963 and its original team consisted of five mutant team members: Cyclops, Marvel Girl, Angel and Beast led by Charles Xavier. While later iterations of the group included characters such as Storm (an African American woman) and Kitty Pryde (a Jewish woman), all of the original characters were white and the bulk of the team has always been comprised of white characters. They represent the mutant community, a racial minority often victimized by discriminatory rhetoric and violent assault. This has led many critics, and a large part of the audience, to read X-Men comics as analogies for the experiences of racial minorities or LGBTQIA+ minorities.[88] As mutants, the X-Men's "anti-oppressive message can be applied to any person or peoples suffering from one or another form of oppression in a hegemonic political system," including the "victims of racist, sexist or homophobic violence."[89] While an argument can be made that X-Men comics promote racial equality because they encourage identification and sympathy with oppressed minorities, Shyminksy points out that "within a genre whose creators and readers are nearly uniformly white males, the X-Men actually solicit identification from a similarly young, white and male leadership, allowing these readers to misidentify themselves as 'other'" and leading comics to "not only [fail] to adequately redress issues of inequality - it actually reinforces inequality" (original emphasis).[90] Because the X-Men are generally young, white males, the comic fails to identify the oppressive hegemony as white and patriarchal while concealing how young, white people can be complicit in its construction. It allows the reader to recognize that the treatment of minorities is unfair on an intellectual level and through this recognition identify themselves as progressive without needing to commit to any self-reflection that would unpack internalized racism, sexism, homophobia or ableism. The X-Men comics inadvertently encourage their readership to interpret the dismantling of white male privilege as oppression, which perpetuates the white male hegemony.

Historically, comics have been written by white, straight, able-bodied and cizgendered men. When that group has been expanded, it has most often included white women first. As Cocca writes, "[dominant] groups have been telling not only their own stories but the stories of those whom they have marginalized as well: whites telling the stories of people of color, men telling the stories of women, heterosexuals telling stories of queers, nondisabled people telling stories of disabled people […] often their lack of authenticity means they're not only inaccurate, but harmful."[91] This book investigates the way that these representations are harmful, and how and why they are constructed as such within their socio-historical context.

The Theory, the Methods and the Framework

This book provides an analysis of the evolution of the representation of gender and race through superhero case studies to excavate the superhero's promotion of dominant cultural values, specifically: conservative and mainstream gender roles as they are determined through the intersection of gender, sexuality and race. By unpicking the dominant reading of superheroes through the socio-cultural context, this book examines how dominant gender roles are reproduced and re-inscribed and how these roles might be resisted.

Discussing Karen Barad's concept of intra-action, Nikka Lykke describes American culture as subsisting of subcultures that "interpenetrate and mutually transform each other" within a dominant hegemony.[92] Cultural norms and values that determine acceptable gender roles, sex presentation, racial relations, etc. are influenced by popular media, the increasing relevance of online cultures (memes, vines, TikToks, etc.), corporate concerns (based on economic trends), executive decisions and artists or creators. All of these influences are themselves influenced by each other and cultural norms and values. This process of influence and intra-action constructs a dominant hegemony that exists as a cultural norm that is both invisible and culturally exalted. Similar to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari's concept of 'folding in', 'intra-action' considers subcultures and dominant hegemony to be continuously interacting as the dominant cultural order folds in or absorbs radical, subcultural elements and purges them of their most politically resistant aspects. Through this process, hegemonic-resistant cultural signifiers become part of the hegemony and re-inscribe dominant norms and values. Similarly, "media forms, such as film, TV, and advertising are notorious for the ways in which they adopt and absorbs oppositional points of view or modes of expression, reframing them in ways that are beneficial to big business and the ruling corporate class."[93] Dominant cultural values, including mass media, consume subcultures and spit them back out in more palatable and normalized formats so that it can be re-packaged and re-sold to mainstream audiences. America, as a country of 326 million people inevitably produces diverse communities and subcultures, but the existence of a dominant cultural narrative that actively works to present the idea of a cohesive and naturally uniform population cannot be ignored. Many cultural and political clashes occur over what the dominant narrative says what it means to be a 'normal' or 'every-day' American. The dominant cultural narrative consistently pressures subcultures to confirm to its norms and values, presenting compliance and 'normalcy' as a route towards respectability and acceptance. While many subcultures respond to and resist these pressures, the dominant cultural narrative co-opts these modes of resistance and sells them back to its audience. Superheroes and comics are also subject to these cultural forces and influences.

Media content can be made with the intention of producing readings that challenge or critique the status quo. Superheroes are multi-authored and transmedial products while comics are collaborative works of art, created by people with their own agendas and outside pressures. While the approach to comics as collaborative art does away with the illusion of the isolated genius, toiling away in their attic, the focus on the collaborators' personal motivations paradoxically prioritizes human individuality over structural influences of power hierarchies. It eliminates the idea of the collaborative team themselves as influenced by structural power hierarchies and how the dominant cultural narrative constructs and is constructed by individuals. In addition to considering the collaborative nature of comic books and their superheroes, it is also necessary to consider a 'production of culture' perspective when analysing comics, as argued for by Casey Brienza's article 'Producing Comics Culture: A Sociological Approach to the Study of Comics.' This prioritizes the context in which comics are produced, taking the production of cultural objects as fundamentally influenced by the power structures within that culture and its interaction with the dominant cultural narrative. This ties into Roland Barthes' prioritisation of the text as the only accessible site of meaning, which the author has no control over once it is in possession of the reader.[94] However, as Stuller writes, "Sex and Gender do not and should not define us or what we do, but a combination of nature and nurture colors our lives regardless. Who we are influences the stories we tell and the stories we want to hear."[95] While the dominant cultural context in which we live influences us as individuals, it is possible for individual creators to be well-versed and conscious of narrative and subcultural codes due to their own position within society. Therefore, they might be able to offer alternatives that provide resistant readings.

Through media content, advertisement and all the other myriad ways in which a culture passes on its values to its people, the audience is also subject to these cultural influences. Shaped (in part) by the cultural landscape, audiences often produce a dominant reading of any given text, depending on their specific socio-cultural and political context. This does not negate the existence of alternative readings created by other audiences, who might exist in different socio-cultural contexts. In turn, alternative readings do not negate the existence of a dominant reading, but automatically imply the existence of the dominant reading. As Bonnie Dow writes, "resistance or opposition assumes that the viewer 'gets' the preferred meaning of the text… prior to resisting."[96] Readings that interpret a text in opposition to a dominant or hegemonic reading require the reader to already be well-versed in codes of resistance.[97] However, due to intra-action, these codes are co-opted and regurgitated by the hegemonic order's folding-in mechanism and lose their power. To get an alternate reading, you first need to understand and unpick the dominant reading.

This process of folding-in covers all the norms and values within a culture, including the understanding of gender and race. Judith Butler writes that gender is "the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts in a highly regulatory frame that congeals over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being."[98] Gender is not biologically defined, but is constructed by culture and its discourse, which frames itself as based on 'natural', biological sex. Additionally, Michel Foucault considers that society's "hold on sex is maintained through language, or rather through the acts of discourse that creates from the very fact that it is articulated, a rule of law."[99] Sex is the biological body and gender discourse claims that this biological body is the foundation for a 'natural' gender binary. Through culture, language becomes layered with additional meanings and connotations based on cultural values, this is what is referred to as discourse. When language is used to discuss sex and gender, this discourse sets the boundaries of the bodies' existence as all the bodies that break the pre-set boundaries are considered unnatural. Butler, when discussing Foucault, further extrapolates "that disciplinary discourse manages and makes use of [individuals, but] it also actively constitutes them."[100] Discourse constructs biological bodies because it is impossible to access the body outside of discourse. Therefore, any description of the body generates our understanding of that body, and thus, the body itself as there is no body that can be accessed outside of that understanding or language. The body constructed through language is then taken as the object that defines culture's gender roles and stereotypes, but actually, it is not possible to distinguish between the two. As Butler writes, "identity is performatively constituted by the very 'expressions' that are said to be its result." Gender is created through the performance of socially acceptable behavioural patterns, which is classified as gender, and which in turn continually produces these socially acceptable behavioural patterns. As Butler writes, biological sex does not create "social meanings as additive properties, but rather is replaced by the social meanings it takes on" (original emphasis).[101] Natural gender roles that determine social functions due to biological imperatives do not exist, they are culturally constructed gender roles interpreted as biologically determined by the dominant hegemonic order. For women, this includes a submissive role, attributes of gentleness and kindness, a soft and nurturing creature. For men, this includes the active role, attributes of strength and power, with the ability to protect and defend the feminine due to an inherent violent nature. For both, these roles are considered immutable and cannot be altered.